044 - Key Notes No. 5: Phish

Trying to answer the squirming question I've never thought to ask: "Why do I like my favorite band?" — and inadvertently uncovering the absolute truths of life

Key Notes is a recurring series in which I write

about music I like

Why is this night different from all other nights?

Well, it’s not different from all other nights, but it’s different from 9,956 other nights of my adult life, which began—per my people’s tradition—on the night of my Bar Mitzvah, 10,006 nights ago.

On this night, as I have for fifty glorious nights spanning the past twenty-two years, I’ll once again be in the company of four men from Vermont, watching them play musical instruments together, live, on a stage.

You could call them a “band.” You could call what they do putting on a “concert.” But those are merely words, and rather feeble nouns at that—the kinds that might conjure a million different mental images by a million different readers, each basing their idea of a “band” and “concert” on their lived encounters: an experimental noise duo in a Soho loft, a ragtime barbershop quartet at an Iowa strawberry festival, an Afro-Latin jazz ensemble in the back of a Berkeley coffee shop. Hoobastank.

Unless you’ve seen these particular four men from Vermont play musical instruments together, live, on a stage, your default concept of a “band” and “concert” will fall shorter than Eddie Gaedel in accurately encapsulating the singular experience that is seeing the band Phish in concert.

I’ll be honest, as I sit here writing this piece, I worry it might be an experience that frustratingly defies absolute description, and that even I—arguably the world’s most famous Phish fan for a six-month period in 2018—may fail to faithfully convey the all-encompassing nature and authentic essence of these unparalleled artists and their inimitable artistry.

Nevertheless, he persisted…

GONE PHISHIN’

Let’s get this out of the way first: Phish is Trey Anastasio on guitar, Mike Gordon on bass, Page McConnell on keys, and Jon Fishman on drums (and occasionally, an Electrolux vacuum cleaner). They played their first show together on December 2, 1983 in the Harris Mills Dining Hall of the University of Vermont, and they’ve played 2,049 shows together in the forty-two years and seven months since—make that 2,050 once spring tour wraps tonight at the Hollywood Bowl.

I arrived on Earth exactly one year and two days after they did.

For the now middle-aged (shudder) millennials who make up my generation, Phish was not a taste inherited from our parents. To wit: the one and only concert my father ever attended in his life was The Dave Clark Five—a group that disbanded in 1970. My mother’s one and only—Streisand at The Garden in ‘94—makes her seem like Lester Bangs in comparison.

Each Phish “phan” can recall their own “phoundational inphluence.” For some it was an older sibling, or perhaps a cousin (not me: I was the older of two, and the only fish I’ve ever seen my Cousin Addie get into is GEFILTE!). My “phirst” exposure came courtesy of the counselors at my sleepaway camp in the Adirondacks, whose own exposure had likely come from their counselors, as had the ones before them. When future jam bandthropologists publish the definitive Phishhead ethnography, I’m sure their population analysis will reveal a clear and direct early lineage from the ur-fan at that first cafeteria show in Burlington to the New England summer camps of the early 90s—migration patterns snaking their way from the shores of Lake Champlain via a network of hemp festivals, disc golf courses, and roadside Stewart’s Shops.

Talmudic scholars continue to debate precisely which “phrequency” (okay, last one) I first tuned into, but my autobiographer maintains it was “Bouncing Around the Room,” the closing track on the band’s second studio album, Lawn Boy, released on cassette in 1990. It’s only natural that in its blend of straightforward melody, playful, bouncy rhythm, whimsical lyrics, and polyphonic harmonies, my adolescent brain found not just an epic sing-along, but a shimmering gateway to a brave new world of sui generis musical fusion.

They say timing is everything, and by the time I had developed a full-blown infatuation with these four men from Vermont—buying up their every studio album and official Live Phish volume on CD (and burning whatever bootleg shows my buddy Mike and I could track down), reading The Phish Book, watching The Phish Movie, checking in weekly to Dry Goods for the latest merch drops, and scouring eBay for old copies of the their ‘90s-era newsletter, Döniac Schvice—it was too late to witness them in their most primal, reverent realm: playing their musical instruments together, live, on a stage.

Burned out from 15 years of prolific recording and relentless touring, the band announced they’d be taking an indefinite hiatus after their Fall 2000 run. It was like I had at last grown tall enough to ride the loop-de-loop at the traveling carnival—only to be told it wouldn’t be coming back this summer due to an investigation by the Attorney General into reports of wage theft and unsafe working conditions.

They also say all good things in all good time, and not two years later Phish resumed touring operations—just as my mommy finally gave me permission to attend rock n’ roll music concerts.

I was a barely legal high school senior on February 28, 2003, when I borrowed Dad’s car, scooped my Greenwich-based girlfriend (with whom I had been bumbling my way through late-stage virginity) and cruised on over to the Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, NY (Schlong Island) for my first Holy Communion with cow funk.

As far as describing the what of Phish, I’m afraid this is as far as I can take you with the power of words alone. Sure, I could whip up some purple prose about the alchemy of their classically-trained, conservatory-honed technical skills combining with their individualized, intuitive geniuses and idiosyncratic, inventive spirits to spin a living, breathing improvisational organism that inhales the collective consciousness and exhales a sacred groove…

I could geek out over their mastery of rhythmic displacement and modal exploration, deep-diving into a Type-2 “Tweezer” and dissecting the interplay between Trey’s soaring leads and Page’s subtle harmonic stabs as they shift from the Pentatonic scale to the Phrygian dominant mode while Mike injects percussive bursts over Fishman’s propulsive, polyrhythmic foundation to create an exotic tension that builds toward a blistering, quasi-arpeggiated peak…

I could off on a masturbatory, reference-laden tangent—as I so often did during my HQ Trivia hosting days—and waste my time with you in getting down to the nitty gritty of a show on the road, with a load-of-shit thesis about the passionate eyes that are energized in the fluffheads of tens of thousands of family berzerkers bobbing along on a velvet sea of olfactory hues, spontaneously synchronizing handclaps while solar garlic stars to rot and shouting graphic translations while their vasoconstrictors come slowly undone…

But you’d likely be left scratching your head, leaving me left reiterating my point, which is: Live Phish is an experience that needs to be experienced to be experienced.

In the meantime, there’s always YouTube. Watch this and call me in the morning:

Okay, so I’ve done my best to define the terms, and I’ve laid out a narrative of my personal history with the band and its music, but I’ve yet to answer the fundamental question that sparked me one terrible night to embark on this musing—recently posed to me by my partner Jewlie, a Phish newbie, who in attempting to better know her true love, thoughtfully asked about a thing he truly loves: “Why?”

My first instinct is to say: Why weigh on a sunny day?

That’s one of the more ridiculous lines in one of the band’s most ridiculous songs, “Weigh”—written by the consensus pick for the most delightfully ridiculous band member, bassist Mike Gordon. Is it a psychedelic koan, meant for contemplation around the bonfire (while the bong fires)? A legitimate plea for spiritual self-reflection and a call for action: to set aside the menial, empirical pursuits of data collection for a cognitive palate cleanse in the great outdoors? Is it simply outright, joyous nonsense?

Or is it all of the above—its disquisitive gumbo the answer to Jewlie’s question?

The full answer is packing heat and comes strapped with bullets:

I like Phish for the sounds they make: a fantastical mélange of genres and idioms bridging rock and reggae and funk and soul and symphonic jazz and sludge metal and ambient electronica and Appalachian bluegrass and yes, even barbershop—spliced from the genomes of Frank Zappa and the Mothers, James Brown and The J.B.’s, The Grateful Dead, Talking Heads, Led Zeppelin, King Crimson, Jimi Hendrix, Herbie Hancock, Leonard Bernstein, Black Sabbath, Bill Monroe, and The Band—all rooted in the overarching principles of “prog.”

I like Phish for the light they generate: both the eye-popping, jaw-dropping displays afforded by the multi-million dollar LED rig their “fifth member,” Chris Kuroda, jockeys from behind the soundboard—composed in real-time to mirror each unpredictable twist and turn of the band’s lengthy explorations—and the impromptu “glow stick wars” waged by the conspiring crowd: thousands of tiny plastic tubes cascading in chemiluminescence amid the collective effervescence.

I like Phish for the culture they cultivate: a carry-over from the Grateful Dead’s open-source ethos of generosity and collaboration between band and fan that freely encourages the taping and sharing of shows, welcomes a caravanning gypsy village of unlicensed vendors that pops up at each tour stop, and supports an anti-corporate cottage industry of graphic designers who pioneered the parodic art of the “logo flip.”

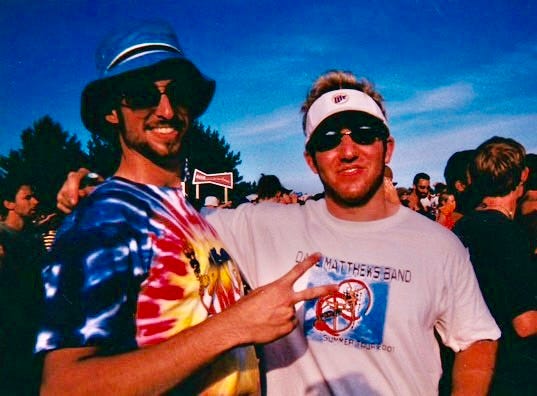

I like Phish for the serendipity of fate their shows seem to shape: both in the random, radiant reunions with familiar faces while navigating the bumper car course of tie-dyed bodies on the way to your seat—and in the exuberant, enchanted unions with unfamiliar faces in your section who become familiar for the next run-in.

I like Phish for the transformative life lessons I’ve instinctively gleaned from their never-repeating, always unpredictable setlists and free-wheeling, utterly unfettered jamming: embrace the unknown, accept what comes, and enjoy what is—whatever it is.

I like Phish for the drugs.

ALLOW ME TO EXPLAIN…

HIGHER GROUND

You should know, I was a “good kid.” The son of the only remaining honest politician who inculcated in me a strict sense of moral dignity (bordering on the self-righteous) and a subconscious fear of straying from the straight path, I didn’t drink or partake of illegal substances throughout high school and into college—because, duh, it was illegal. Both my parents being teetotalers only further curbed any urge to exercise my right to party. A joke in my old stand-up routine went: “I didn’t have a liquor cabinet in my house growing up. The best my friends and I could do for kicks was raid the spice rack. ‘Top shelf’ in the Rogowsky family meant where Mom kept the manila envelopes.”

As such, I attended my first baker’s dozen or so Phish shows Stone Cold Steve Sober. When recreational marijuana laws started loosening up in the 2010s, I began dabbling in edibles, which seemed to beautifully suit my neurochemical constitution and relieve the neurotic symptoms associated with my as-yet-diagnosed OCD and ADHD. Needless to say, taking in a Phish show on the wings of a cannabinoid high was a revelation. The music and mythos of my beloved band, which I had spent over a decade infusing into my heart and soul, was now pulsing a little louder, shining a little brighter, vibrating with love and light that I could really feel, man.

Getting comfortable with cannabis helped me overcome my crippling anxiety around “not being in control.” Chalk it up to the D.A.R.E. program and the after-school anti-drug PSAs that proliferated in my post-Reagan youth, but I’d been convinced that so much as making eye contact with someone under the hallucinogenic influence could charm me into following them up onto the roof to test our immaculately-conceived powers of flight. But Phish had taught me that the trick is to surrender to the flow. I imbibed, and I had survived—now I was ready to get even more heady.

The set and setting of my first psychedelic trip was Phish at Madison Square Garden on Night 2 of their 2017 New Year’s run. Acting as administrator, my friend Steph popped an LSD-laced Altoid into my mouth on our way into the venue. I tried to remain patient as my thoughts buzzed with anticipation for what magical mysteries I might conceivably comprehend once the doors of perception parted. The timing of my peak couldn’t have been better planned—the elevator of my mind arriving at the penthouse just as the band segued into one of their wickedest jam vehicles for the second set closer, “Split Open and Melt.” The Garden split open, and I melted into the space between the spaces. Adorably, I remember thinking to myself as I plunged below the water line, “Ohhh, so that’s why they named it that.”

Here’s what I’ve come to understand about Phish, the music they make, the concert spectacle they curate, and the scene that has coalesced around them—and why distilling the entire experience into an essential evocation proves so elusive: Phish is not a band at all; they are a drug: not strictly in their habit-forming potential (evinced by the many phans who boast show counts in the three-to-four figures), but in their psychedelic ability to act as a conduit to the here and now—a portal to the present moment, connecting us to the conscious awareness of what it feels like to simply “be.”

Locking into a jam is to become aware of awareness itself. Riding the sonic waves emanating from the stage is to merge with the moment—in the very moment it arrives. Jumping into an improvisational vortex is to surrender all sense of control, certainty, and expectation. Every note played is perfectly placed and right on time, born from almighty intuition, delivered to our ears on the numinous winds of whim.

Live Phish is the soundtrack to the Tao. It’s effortlessness in action, it’s perfect imperfection, it’s both nonsense and all-sense, both sacred and absurd. Live Phish is Om. It is consciousness entertaining consciousness. It’s four separate minds merging in a unified whole, acting as a catalyst for an ecstatic state of collective ego transcendence and eternal presence that, due to the inescapable distractions of the outside world and the constant thrum of our inner static, is nearly impossible to attain in any other of life’s arenas—except the one in which the band’s playing.

Phish shows have often been written about as a “religious experience,” but as a Jew who has spent countless Shabbats and High Holy Days in synagogue, ostensibly communing with the Creator, I can speak to a key difference between the two: in temple, we’re told about the divine and we talk about the divine; at a Phish show, we make direct contact with it. The sublime moment of quantum fluctuation when one song dissolves into the ambient ether before reemerging as the faintly recognizable beginning of the next is nothing less than Creation made manifest—God waving his hand and bringing forth living creatures of every kind: here, a Llama; here, an Antelope; here, a Possum; there, Vultures; there Lizards; there, a Turtle in the Clouds.

Maybe I like Phish for the radical role they unwittingly played in reconnecting me to myself—and to the Self. Seeing those four men from Vermont play their musical instruments together, live, on a stage, and on the right dose of the right drugs, is what squeegeed my third eye and jumpstarted my spiritual journey. Phish introduced me to psychedelics. Psychedelics introduced me to elevated states of being. Those states of being crystallized for me the concept of living in the moment and formed the first cracks in my ego’s tormenting and distorting grip on reality—cracks I later pried open in the Hoffman Process to complete my breakthrough: shattering my shadowy false self and reconstructing me as my fully integrated, authentic self.

Or maybe the answer can never be known… and maybe that’s the point. Maybe the ineffability is the answer?! By George, just as the lights come down and the band takes the stage, I think we’ve got it! Perhaps in the impossibility of perfectly pinning down the why, I will remain forever aware of the infinite possibility of the present moment—and the limitless creative potential of the what that comes next in my own extended improvisational jam… otherwise known as…

MY LIFE! (Borat voice)

EPILOGUE AND EVOLUTION

Eighteen months after their return from Hiatus on New Year’s Eve 2002, Phish called it quits again—this time, they said, for good. The band’s growing popularity had placed mounting pressure on their touring operation and given way to a dangerously unrestrained backstage environment. In a written statement to fans, frontman Trey cited the band’s deep love and respect for their own health—and the health of their relationship with their audience—as the determining factors behind this final decision. As quickly as Phish had been resurrected in what felt like a gift from the cosmos for my 18th birthday, they were laid to rest once more.

In December 2006, Trey was pulled over in upstate New York and arrested on DUI and drug possession charges. Unbeknownst to most outside his inner circle, he had been battling opioid and alcohol addiction for many years. He would go on to spend the next two under the supervision of the Washington County Drug Court, completing community service and, crucially, getting sober. In saving his own life, Trey was able to find the strength to get the band back together—this time, for good—where I reunited with them on a rainy May night at Fenway Park in 2009.

In his revitalizing sobriety, Trey reclaimed the energy once consumed by his addictions and redirected it into his songwriting, ushering in a prolific new era and casting a fresh lens over his lyrics—a hopeful, humbled perspective grounded in gratitude for the present moment. And it makes sense. Where drugs and alcohol might once have been a way to numb the pain of the past or disassociate from the anxiety of the future, sobriety is all about finding contentment in the present—and then staying there. As one of Trey’s newer additions to the Phish catalogue, “Everything’s Right,” attests: “Focus on today and you’ll find a way / happiness is how / rooted in the now.”

I’m coming to life with a new sober perspective of my own, which has unlocked a torrent of creative expression and enabled me to access mindfulness and presence in ways I—a dizzyingly neurotic, terribly impatient, self-hating maniac—never imagined possible. For the reasons I outlined earlier, I thankfully never struggled with drugs or alcohol, but that’s not to say I wasn’t spared from developing an appetite for self-destruction. My inner demons were sated by relentless self-recrimination, suffocating self-pity, nagging insecurity, paralyzing codependency, and spiraling self-doubt. I was addicted to negativity in all its insidious forms, and I coped with a frenetic work life, a frantic dating life, endless commiseration with my equally neurotic friends, and an almost pathological aversion to the present moment—constantly ruminating on the past or worrying about an imagined future.

With no more to give and the well dry, the pavement worn and my brain fried, I did my own version of “checking into rehab” at the Hoffman Institute’s retreat center, tucked into the Sonoma Mountains in Northern California. I sobered up from negativity, reconnected with my innate divinity, and left feeling like a born-again human. It wasn’t twelve steps, but it felt like one giant leap. Seven days in an entirely undistracted, self-reflective environment without my phone—and nothing but daily, hyper-concentrated doses of psychodynamic therapy, guided visualizations, expressive release work, and mindfulness practices led by rigorously trained facilitators—accomplished for me in one week what fifteen years of sporadic therapy couldn’t.

My morning sadhanas, nightly gratitudes, and daily Jnana yoga practice—in mental dialogue with the teachings of Michael A. Singer, Ram Dass, Don Miguel Ruiz and Hindu’s Helping Friendly Book: the Upanishads—have only further strengthened my spirit in these ten months since returning from Hoffman. It truly feels like every day is a great day—and yet, tomorrow will be even greater, because I now intrinsically grasp the knowledge I had lacked: every experience I have in a day—every call with Jewlie, every conversation with a stranger, every walk with my dog, every pot of coffee I brew, every egg scramble I make, every quiet thought I have to myself—makes me greater than I was the day before.

Hence, EVERY DAY IS THE GREATEST DAY! EVERY MEAL IS THE BEST I’VE EVER HAD! EVERY OUNCE OF LOVE I FEEL FOR MYSELF AND MY BELOVED EXPANDS EXPONENTIALLY!

Q.E.D.

Lately, I’ve been running into friends who haven’t seen me in a while, and they all seem to to think I’ve lost weight. Maybe a little. I’ve been more mindful about my diet, and I haven’t been weight training or working out like I used to. Instead, I’ve been working in—you should see what my shakti can bench! I’ve flipped myself upside down and inside out, reaching the point where I’ve somehow found the focus and motivation to crank out over 3,000 words about Phish in three days 4,500 words about Phish in four days. Sometimes I stop and wonder, “I don’t know where all this energy is coming from???” And then I remember, “Oh yeah, I did the work, I continue to do the work… this is my return on investment!” Sure beats the bets I made on Litecoin and Lastings Milledge…

I’ve even reached the point where I viscerally get what it means to be unconditionally happy—knowing in my bones that I am whole and complete within myself; that outsourcing my mood to external circumstances is basically punching a one-way ticket on the struggle bus to Bummersville; that I will always be okay as long as I’m okay with me alone. The first book I read post-Hoffman was Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning—and that’s when it hit me: if he could survive the Holocaust deprived of anyone or anything other than the barest of Maslow’s necessities, I should be able to jive, strive, and stay alive through my 40s.

What is the inevitable conclusion of such a bold declaration, in the context of this essay? What is the central theme to this everlasting spoof?

I’ve even reached the point where I don’t need Phish.

That doesn’t mean I don’t still love—in fact, as I’ll soon further explain, I love more. That doesn’t mean I’m any less grateful than I’ve always been—and always will be—for how seismically they shifted the direction of my life, for how profoundly joyful they’ve made me for so many thousands of hours, for what they taught me about not bowing to conventional pressures, not taking things too seriously, staying true to my vision, embracing my outsider status, and the reinvigorating benefits of taking a break.

I just don’t need them in the way I did before: as an entry point to presence, connectedness, and conscious bliss. The live Phish concert experience—acid and all—rended my veil of ignorance and realized my Ego transcendence, diverting me from the “straight path” and leading me to my current privileged perch in the seat of the Self. In a self-destructive twist, Phish paved the way for my transcendence of Phish.

I’m still good for a few shows a year, going sober or digging into the fun dip, depending how I feel—and always with the utmost respect for the trip. I genuinely love the music. I scream my lungs out with the best of ‘em on the call and responses, and I always dance like nobody’s watching—because nobody ever is. It’s all gravy for me now: pure, moist green organic, unfiltered fun. While no longer requiring of Trey’s piercing, climbing sustains soaring over Page’s crescendoing staccatos—or Mike’s modulating bass bombs exploding over Fish’s biting snares and shimmering crashes—to access what the Yogic mystics describe as “ever greater joy,” it’s still one helluva way to spend a Sunday night.

In finding my self-love, I’m able to wholeheartedly radiate that love to others. Extending that deeper love to Phish has meant nurturing an emotionally healthier relationship with my fandom.

I used to engage with Phish from a place of expectance and entitlement; as an analyzer and a critic. I’d come into shows hoping they’d play certain songs, trying to call set openers and encores, thrilling to accurate predictions, and obsessively following the setlist on Phish: From the Road. I’d take it personally if the band was “sloppy” and get weirdly upset when Trey flubbed a note or Mike forgot a line. I’d scroll through fan forums, read anonymous arguments, and watch some dude on YouTube breaking down each night’s show on a whiteboard in his bedroom, ranking the songs and sets on a 1-10 scale. I’d always complain about the new album, and I’d bemoan “Christian Rock” Trey—half-jokingly agreeing that he was “better on heroin.”

In hindsight, I wasn’t being kind to the band, sure, but I also wasn’t being kind to me. Expectations, I’ve since come to learn, are nothing but pre-mediated resentments. Little did I know that in playing the role of an aphishionado, I was actively undermining my own enjoyment of the thing I claimed to love more than anything in the world. Even the notion of identifying with a “favorite show” or “favorite song,” I came to realize, was an egoic illusion at its spiritual core—because any preference I hold is ultimately just a reflection of my identity.

The absolute truth is this: the best show ever is the one I’m at. The best song of all-time is the one being played. The best moment of my life is the one happening right now.

Phish’s latest studio album—their sixteenth, released last year—is titled Evolve. In a way, this feels like an obvious statement. Artists are people. People grow (and get sober). As artists evolve, so does their expression—a fact I’ve come to honor in my newfound sobriety, and as an evolved fan.1 Part of my personal growth and evolution has been driven by the simple act of questioning my previously held assumptions and beliefs. Through introspection, I came to recognize the self-defeating paradox inherent in my negative pattern of making judgments: to criticize a band so deeply entwined with my own journey—one that had taught me the very meaning of presence—would be to criticize not only myself, but the moment itself.

But the moment is perfect! The moment transcends! And when the moment ends, I feel winds blowing differently than ever before, pushing me further to the shores of absolute truth: I am perfect. Phish is perfect. Only Ego hears the flubs.

Nothing is wrong when everything’s right.

Will I ever pretend to prefer “Sigma Oasis” to “Suzy Greenberg”? No. But here’s yet another absolute truth that recently sparkled within me: while that first whiff might stink, in few years I’ll be screaming for “More!”

"The absolute truth is this: the best show ever is the one I’m at. The best song of all-time is the one being played. The best moment of my life is the one happening right now."

Nicely said. I've also been the kind of Phish fan who's bemoaned "Christian Rock" Trey and all the usual Phish gripes from being too online and the band's message board culture that I grew up with. Then my brother and I took my mom, a retired middle school music teacher, to her first show at the Peterson Center in Pittsburgh in 2017, right before the Baker's Dozen. In our row, I got stuck next to a guy who was a super miserable/entitled complainer. He even looked like the Comic Book Store Guy on The Simpsons, taboot. That's when I realized how lame that whole schtick was. My brother and I were enjoying this wonderful moment with my Mom and trying to show her this wonderful world that we love so much, and this guy can't stop leaning over to point out something he didn't like. Life's too short to have a Debbie Downer like that in your ear in those moments, and I realized I didn't want to be that guy down the line.

Great read. Thanks for writing it.