063 - Noteworthy: Confessions of A New Hobby

TRIGGER WARNING: This piece contains descriptions of a Jew's love for money that may be unintentionally validating for antisemites.

What did you do today?

Me? I went to the bank with five $100 bills and kindly asked the teller to exchange them for five hundred $1 bills.

I then went home and spent a joyous forty minutes at the kitchen table carefully examining each bill for curious serial numbers or vintage series dates.

Do I make you horny, baby?

I had a backstory at the ready, had the teller asked, “Why?”1

“I work in the prop department for Law & Order: SVU, and we’re shooting a scene at a strip club.”

Not that a cover was even necessary — there was nothing improper about the picayune particulars of my peculiar, pecuniary petition — but I figured a white lie would be easier far less embarrassing than admitting the truth, which is...

I’m a numismatist.

Really, I’m a collector of all things. Always have been. At various points in my life I’ve collected sports cards, comic books, comic book cards, sports books, celebrity and athlete autographs, postage stamps, Starting Line-Ups, gems and minerals and fossils (here’s lookin’ at you, trilobite), matchbooks, glass bottles, historic newspapers and magazines, Playbills, political buttons, Wheaties boxes, Coca-Cola cans, “Got Milk?” ads, Hot Wheels, McDonald’s Happy Meal toys, Beanie Babies (errors and rarities only), vinyl records, vintage t-shirts and hats, and literally anything related to baseball (programs, yearbooks, scorecards and their mini pencils, pins, pennants, posters, pocket schedules, bobble heads, ticket stubs, team sets, seat cushions, stadium cups, ice cream sundae mini-helmets, player model gloves, game-used bats and balls, Cracker Jack prizes, even peanut butter jar lids) — in addition to coins and paper money, aka numismatics.

At the risk of censure from the Anti-Defamation League, money has held a distinct fascination for me ever since I first clutched a shiny nickel in my chubby, grubby baby hands.2 The fascination goes beyond money’s inherent mystique as a species-defining civilizational triumph of collective mythmaking — though a discussion of its ontology is one I’d happily indulge should you find yourself seated next to me on a cross-country flight. And despite being born at the precise time and place to seem the actual demon spawn of modern American capitalism itself — mid-1980s New York City — my fascination has little to do with the prosaic desire to acquire it.

Even before I fully understood how money can be exchanged for goods and services, I was taken with its pure physicality — the shapes, sizes, weights, textures, colors, and even smells of currency providing a face-value feast for the senses. Why trade money for collectible trifles and trinkets when the money itself could both satisfy my curiosity and stimulate my neurodivergence?

I look back fondly on the countless countless kid hours I spent sorting through the change that would accumulate in my dad’s sock drawer, marveling at the mosaic of silver slivers gleaming among the vast tinted spectrum of the humble penny — freshly-minted fiery reds and lustrous golden-blondes mingling with the warm brunettes and patinated blue-hairs of the older, copper crowd.

I’d wonder why certain coins had small letters printed beneath their dates, while others did not… why pennies and nickels were smooth around their circumferences, while quarters and dimes had ridged edges3... why quarters dated 1976 ditched the typical spread eagle motif on the tail for a colonial drummer boy… why pennies minted before 1959 featured stalks of wheat on the reverse instead of the stately memorial to the man on the obverse…

My Uncle Alan was largely responsible for nourishing this flourishing new hobby of mine, thanks to the many gifts he’d deliver me upon his return from some fantastic, far-flung voyage to Moscow or Macau in the form of exotic, leftover change: strangely engraved coins and cash in flashes of red and blue and purple and green — greens that were greener than any greenback I’d seen — bearing portraits of women in crowns and gowns and men in Mao suits, Stalin tunics, and Nehru jackets — none of whom I recognized, all presumed dead.

The sheer volume in variety of banknotes from countless countries in all their many denominations was more than enough to trigger my collector’s instinct latent OCD undiagnosed autism, and the deeper I got into these collecting weeds, the more popular I became at school.

lololol totally jk!!!

But I did start to become more knowledgeable about the kinds of things verrrrry few people — let alone 11-year-old kids — would ever care to know, discovering the answers to some of those questions that had earlier stirred me — the small letter stamped under the date on certain coins is a ‘mint mark,’ identifying the specific branch of the U.S. Mint where the coin was struck — while uncovering answers to questions unasked — pennies produced before 1982 contains 95% copper, making each one-cent piece worth three cents in the current copper market.

I’d beg my dad to take me to coin and stamp shows at the Westchester County Center — more like museum visits than shopping expeditions, since I didn’t have the money to buy… money. Once on a family trip to D.C., I positively geeked out during a tour of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing — “The Buck Starts Here!” — securing a bag of shredded Benjamins from the gift shop I long cherished as a prized souvenir.

And then, I grew up — and largely grew out of my dorkier obsessions. After decades tucked away in the attic, the Wheaties boxes and Coke bottles and bountiful bins brimming with myriad tchotchkes now boast their own impressive collections — of dust. But when it came to coins and paper money, I could never fully shake my magpie instinct. Over the years, I continued checking my change, sequestering copper-core pennies from their contemporary, copper-plated cousins and squirreling away star notes to my own sock drawer.

Recently, without remembering exactly how, I fell face-first down a delightfully strange new rabbit hole amid the warren of numismatics: fancy serial numbers.

Apparently, in the eon between my pre-Internet, early 90s childhood and today’s hypersaturated digital society, the confluence of online forums, social media, and ecommerce platforms has breathed fresh life into a once-musty hobby. Account for the normalization of neurodiversity and a culture in the grips of terminal-stage capitalism, and voilà — an entirely novel and shockingly valuable class of currency collecting was born.

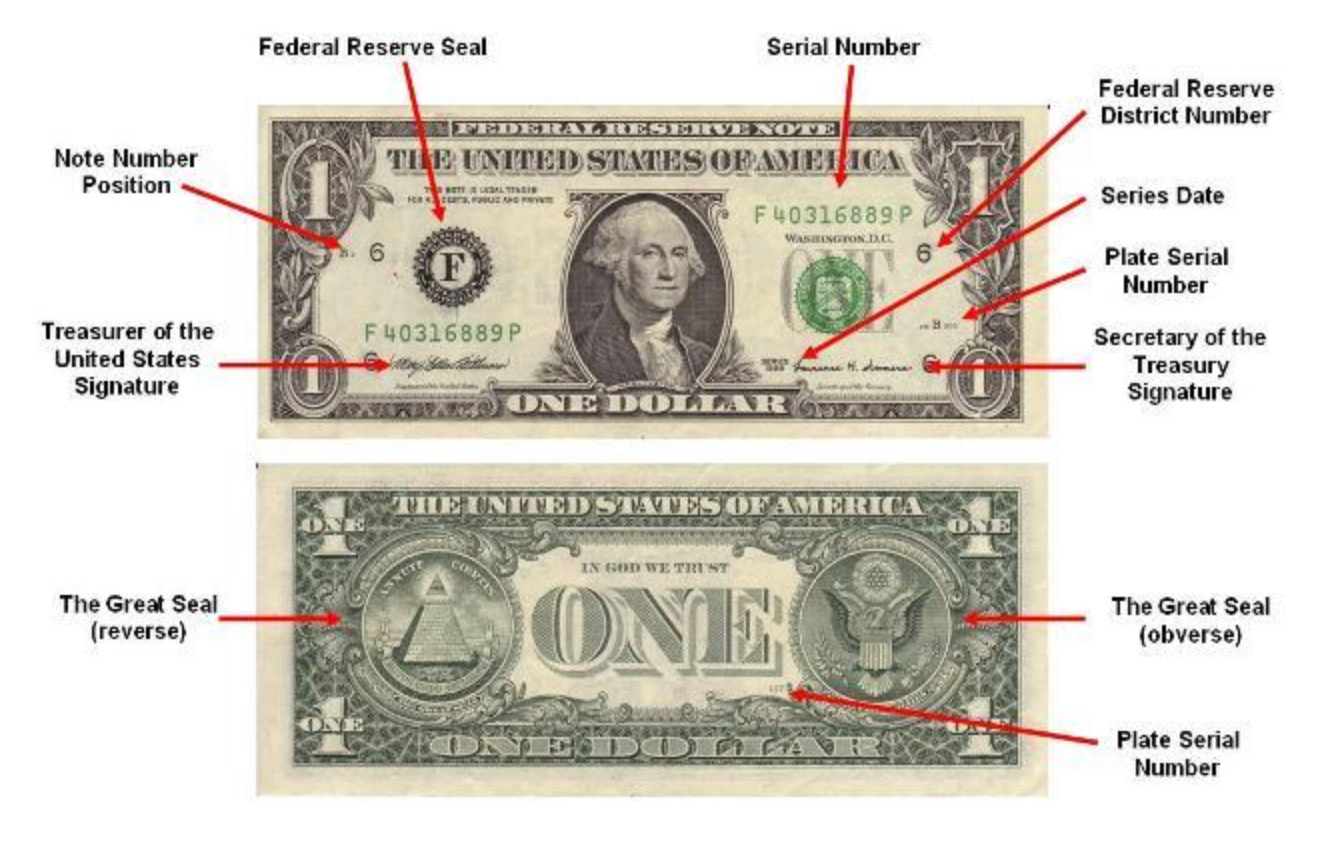

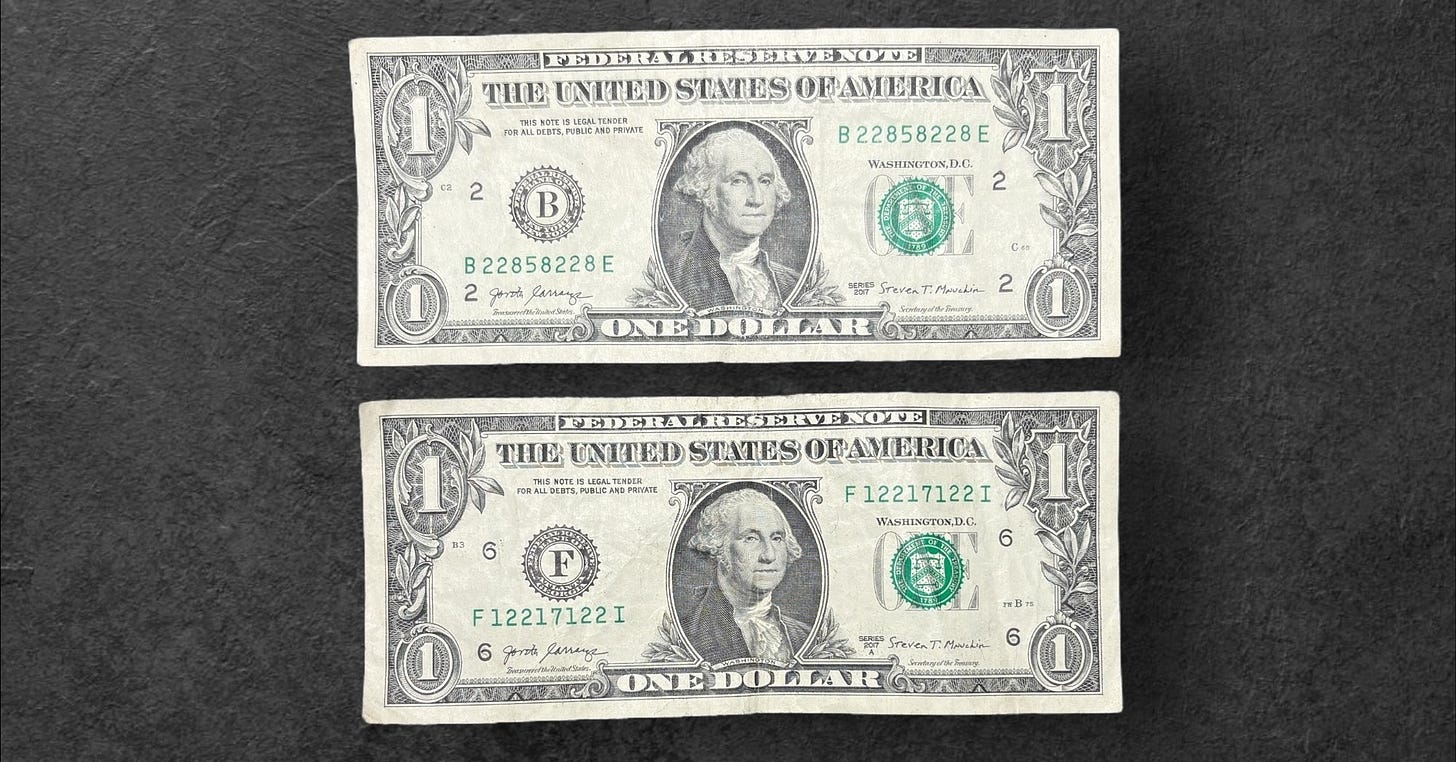

It’s possible you’ve never lingered long enough over your allowance to notice, but every dollar bill printed by the Federal Reserve contains a complex array of numbers and letters on its face. The green, eight-digit string found in duplicate is the serial number, denoting the order in which the bill was stamped, sealed and sent out for circulation. In the example below, that 40316889 number means this was the 40,316,889th dollar bill that came off the line in its particular print run (corresponding to a year and issuing bank).

Now that you understand that, try to understand this: people are paying big bucks for smaller bucks if their serial numbers happen to be… “fancy.” Fancy has become the hobby’s catch-all adjective for anything interesting, unusual, or noteworthy in the number’s pattern. Terms like “radar” (number is same forwards and backwards), “binary” (consisting of only two distinct digits), “ladder” (numbers arranged in ascending or descending order) “repeater” (numbers repeating in combination), and “birthday note” (numbers conspiring to spell out a calendar date) have become standardized by hobbyists in the Internet-era, who share their finds on Instagram, YouTube, and Reddit — and sell them on eBay and Etsy.

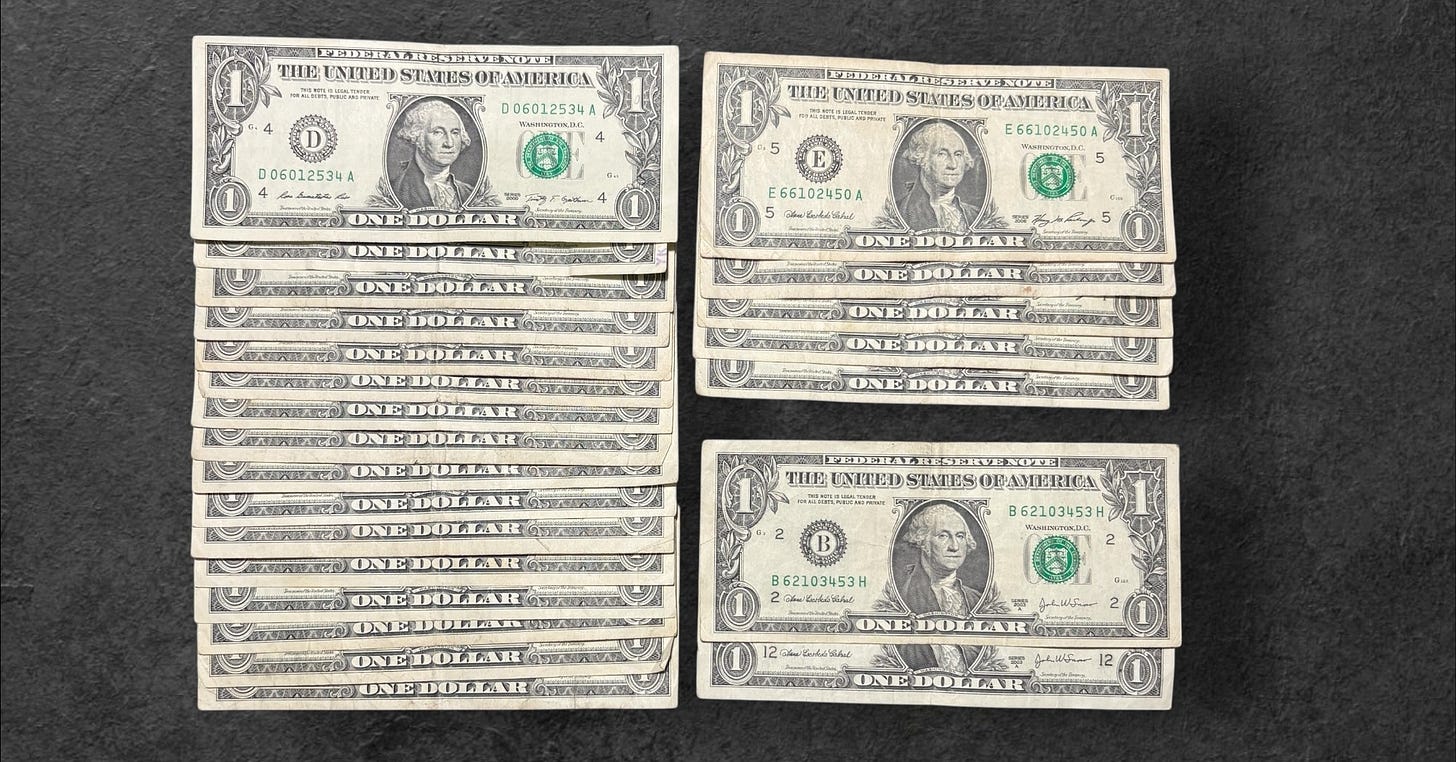

Recognizing the absurdity of what was happening here, I snapped into action — scanning the scant bills in my wallet before tearing open the mattress to get at the rest of my hoard. Having left no serial unturned and still jonesin’ for another score, I kickstarted a scheme to cycle five hundred dollars on an endless loop: five $100 bills to five hundred $1 bills, and back again to five Ben Franklins — mixing in those terrific Thomas Jefferson twos and an occasional 20-pack of fivers, for the gosh darn heck of it. It’s not technically money laundering, but it sure feels like it!

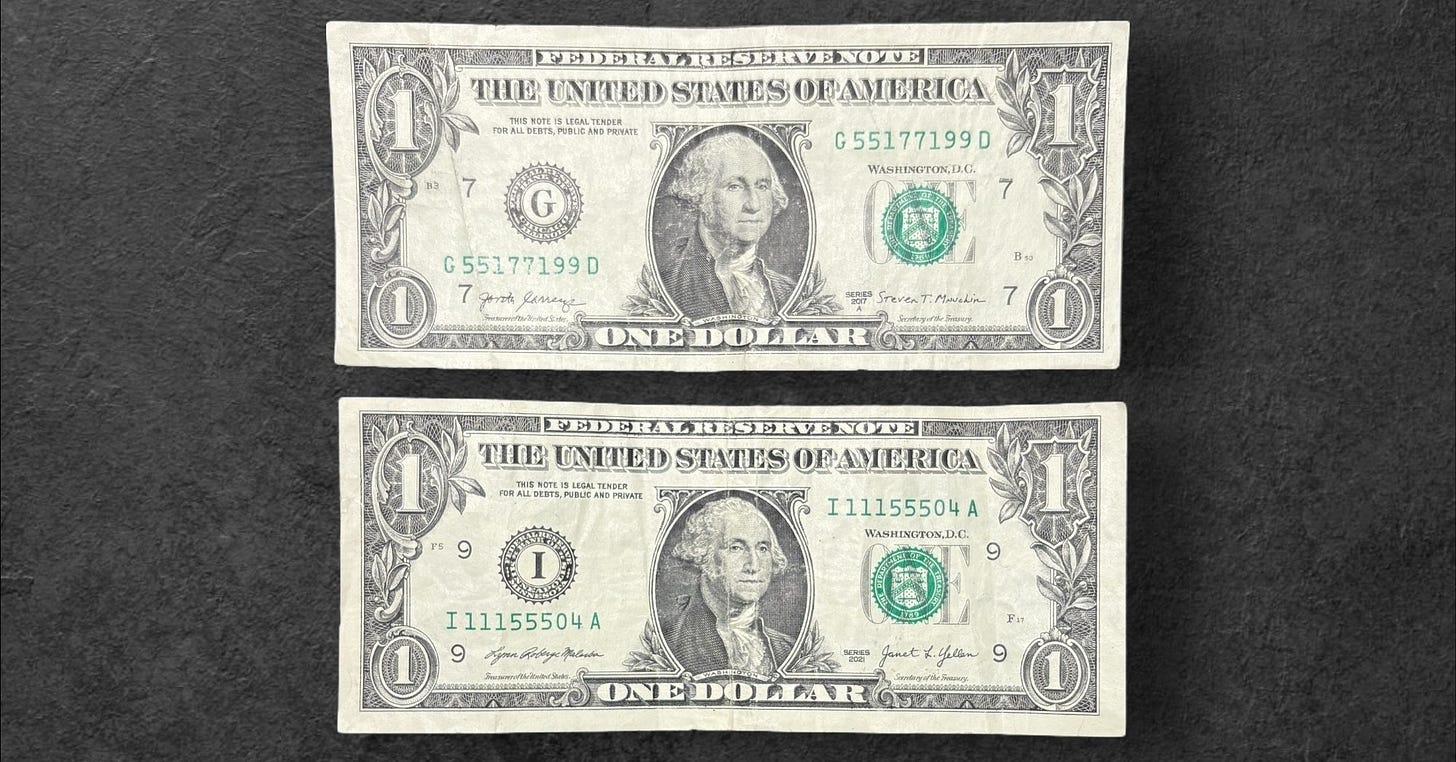

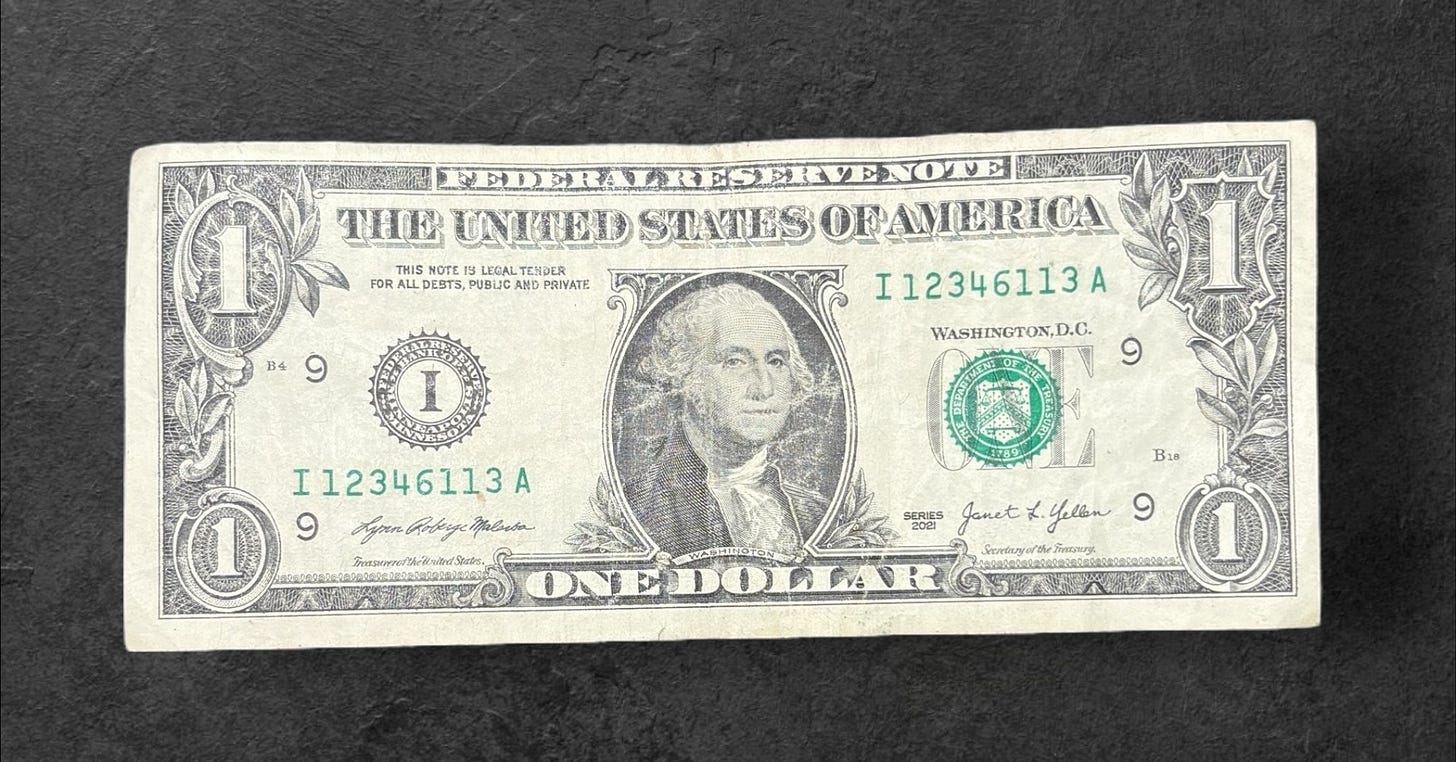

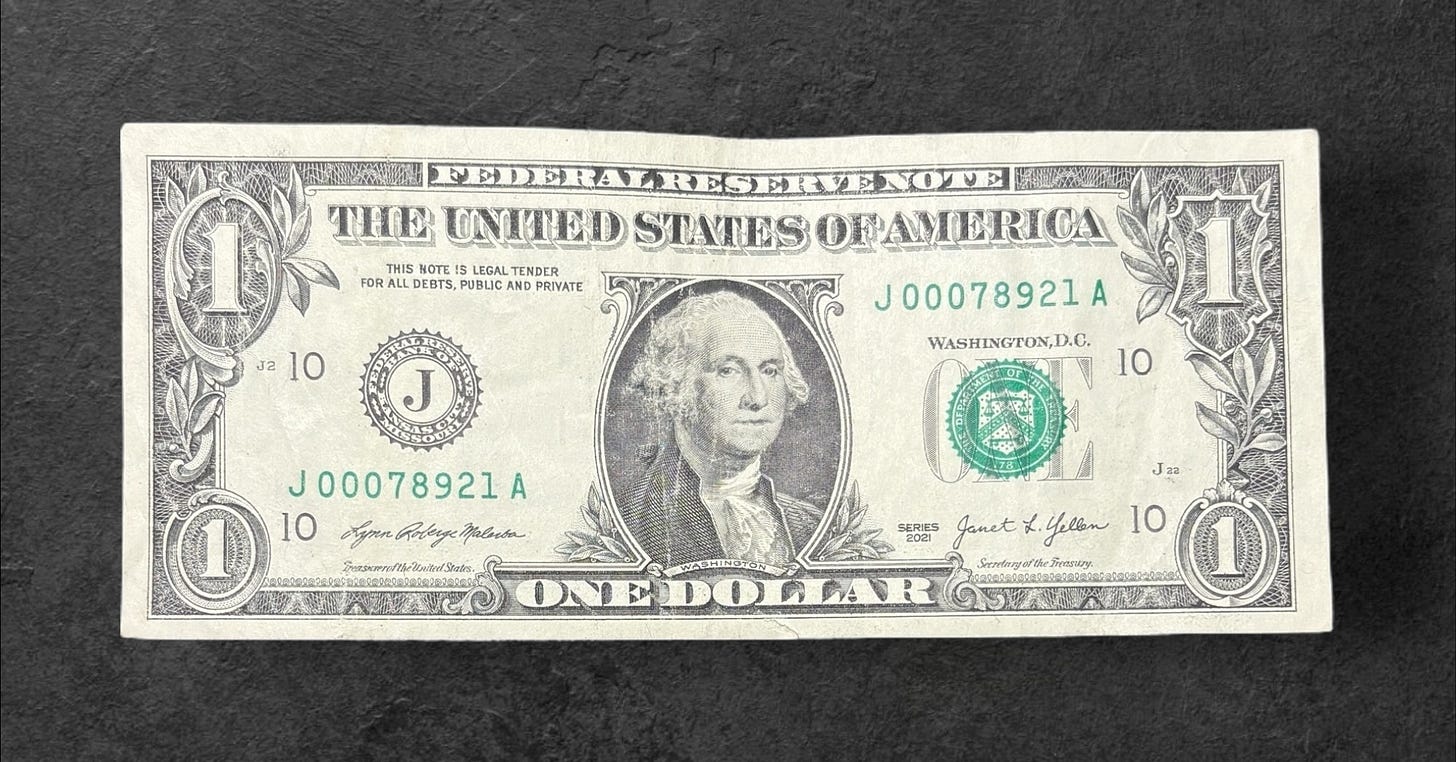

Below is a report of what I found in today’s haul, and here is where you’ll find eBay listings for the fancy bills I fished out. At the very least, I hope I’ve provided an entertaining introduction to a niche subculture heretofore unknown to you. At most, may I’ve inspired you to drop everything (but the baby) and join me in this no-cost, all-fun, infinitely rewarding treasure hunt — one that might literally have you laughing all the way to the bank.

May one day you will,

know that incomparable thrill,

of getting two bucks

for a one dollar bill.

THE STATCASH® ANALYSIS

Out of five hundred bills, just twenty-four were printed before 2010 — sixteen from 2009, five from 2006, two from 2003 — and only dates to the 20th century (1999).4

I’my toying with the idea of stockpiling some of these older bills and trying on a new personality as “the guy who exclusively spends Obama-era cash.”5

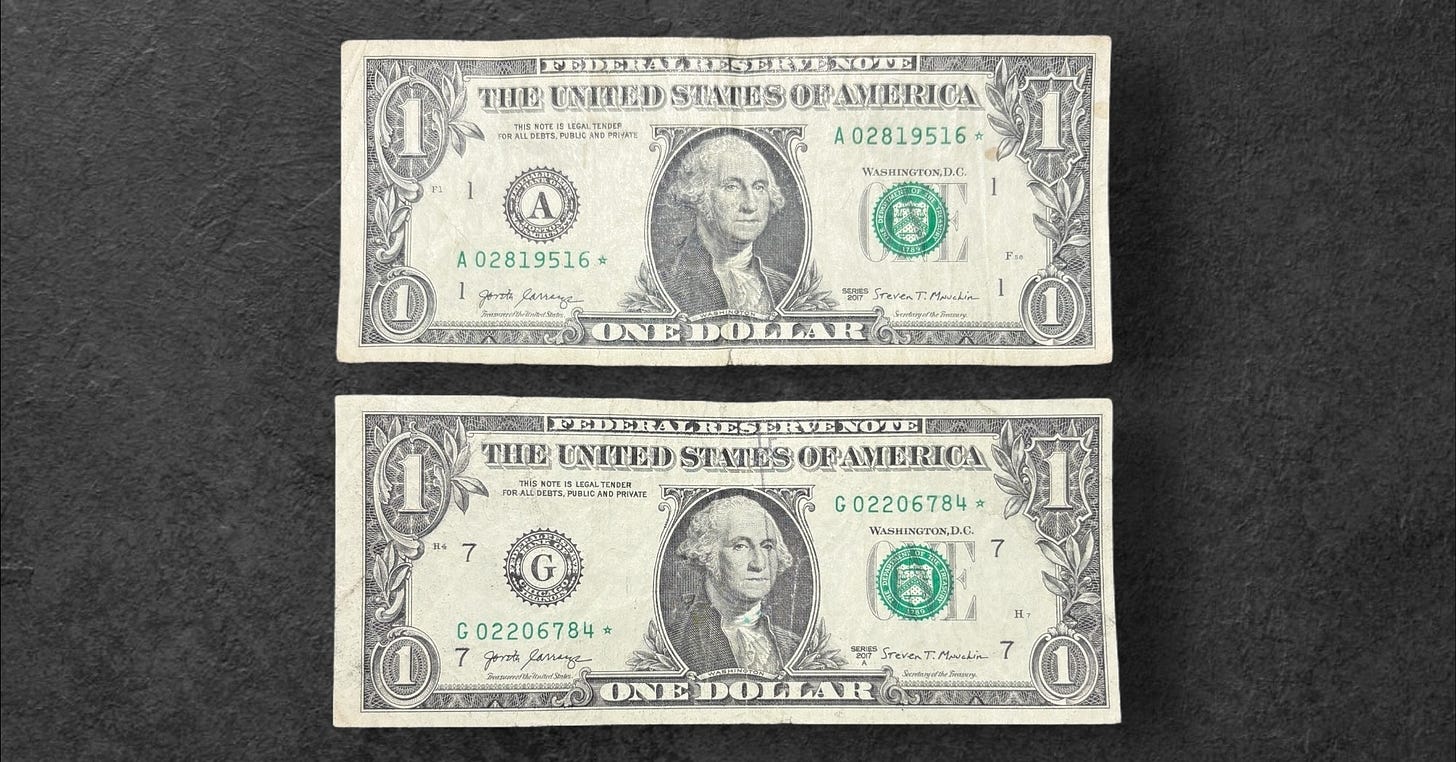

Two were “star notes” — notes that were re-printed to replace faulty ones on the original production run. Because no two bills can have the same serial number (for accounting purposes), they’re reprinted with a ☆ in place of the final letter.

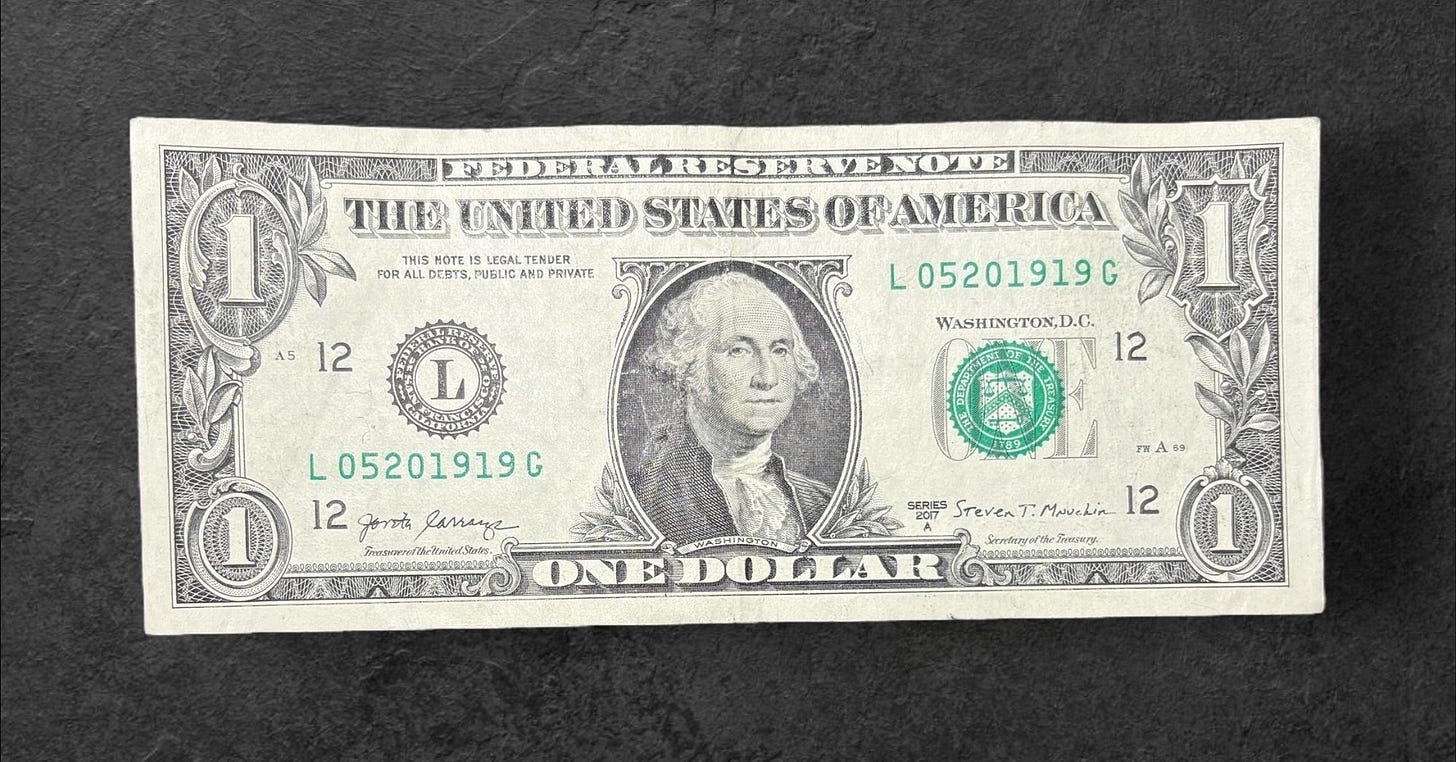

One was a “birthday note” — the 050201919 translating to May 20, 1919 in autistic arithmetic. Expecting an epic bidding war among the remaining 106-year-olds!

Two were “trinary” — containing three distinct digits (2, 5, 8 and 1, 2, 7).

One was a highly coveted “binary” — containing only two (1, 9).

One was a “triple-double repeater” or “three pair,” featuring three sets of doubly repeating digits (55, 77, 99). Another was a “triple repeater,” featuring two sets of triply repeating digits (111, 555).

One was a “partial ladder,” climbing half-way up with the first four digits (1-2-3-4).

One was a “broken partial ladder,” meaning it contained eight distinct digits which, if rearranged, could be said to form a partial ladder (0-2-3-4-5-6-7-8).6

Only one had a serial number under 100,000 (00078921), which I found mildly interesting.

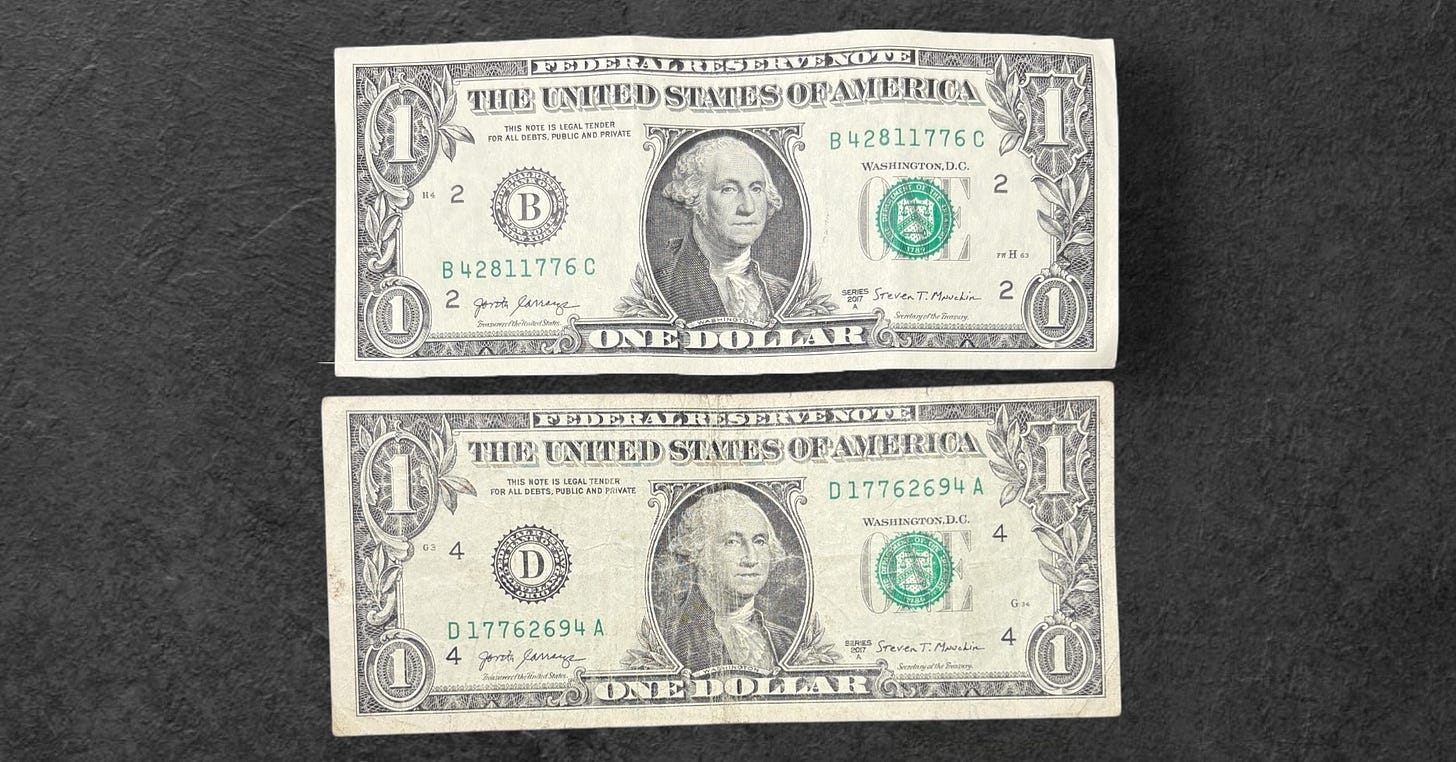

I found two that included the year 1776. Now, if these were 07041776 or 17760704 — aka “‘MERICA NOTES” — I bet I could get some Toby Keith-loving, True Red-White-And-Blue Patriots® to bid them up well into the four figures.

But they’re not, so I’ve got ‘em listed at $7.76, or best offer. Make one now!

She didn’t.

To address the elephant in the sukkah: the fact that I’m Jewish has nothing to do with this. A) Like most stereotypes, the one about “Jews loving money” is patently idiotic… because ALL PEOPLE LIKE MONEY, and B) Keep reading…

“Reeded” being the technical term, and the historical reasons for which were to prevent counterfeiting and discourage clipping

Shoutout Larry Summers!

Shoutout Timmy Geithner!

It should be noted: this is a term and an entirely new collecting subcategory I made up for myself, just now. You’re welcome to start using it — and collecting it, too!