059 - A Place for My Stuff: Vol. 4

The height of my academic career was the nadir of Scandinavian scholarship

Every so often, I’ll boot up an old laptop to see if there’s anything interesting to be excavated. The most recent excursion into my digital past turned up a most curious, decades-old .doc from my junior-year semester abroad in Copenhagen.

Copenhagen in 2006 was still many years away from becoming the widely desirable, highly Instagrammable destination it is today: a quiet backwater lacking the raucous reputation of far more popular study abroad locales like Rome, Barcelona, or Sydney. But my schmuck friends and I made our own fun, namely by making fun of our seriously minded and sober in mien professors.

To say I “studied” abroad is a bit of a misnomer. The principal aim of my Scandinavian semester was to meet sexually liberated Danish women, eat lasciviously iced Danish pastries, and get a good, long look at that Little Mermaid statue… and Odin help any professor who tried to distract me from that mission with “homework” and “assignments.” My modus operandi was to exert the bare minimum effort required to secure a passing grade.

With one notable exception…

Nordic Mythology was the singular course in the catalog that had a prayer of capturing my attention and imagination. It was taught by a jolly old fellow sprouting a Viking Age beard and sporting Cosby-esque sweaters that strained to stretch around his rotundity named — get ready for this — Morten Warmind, who had no mind for attempting to corral the American idiots running rampant in his classroom.

Instead, Morty required us to not only read, but also write a final paper about the Poetic Edda — an anonymous collection of skaldic poetry dating from the 10th century — and its 13th century companion the Prose Edda, which taken together are considered the primary source textbooks of Norse mythology.

Did I complete the readings? Hellllll nah. Did I skim them enough to write a ridiculous parody infused with references to 80s baseball players and 90s video games? Yes, yes I did. Reviewing this paper nearly twenty years later, I’m quite impressed with my younger self to commit to such a supremely ludicrous bit over so many pages. Prof. Warmind must have been impressed, too. Despite having no possible way of comprehending 90% of what I wrote, he gave me an A-.

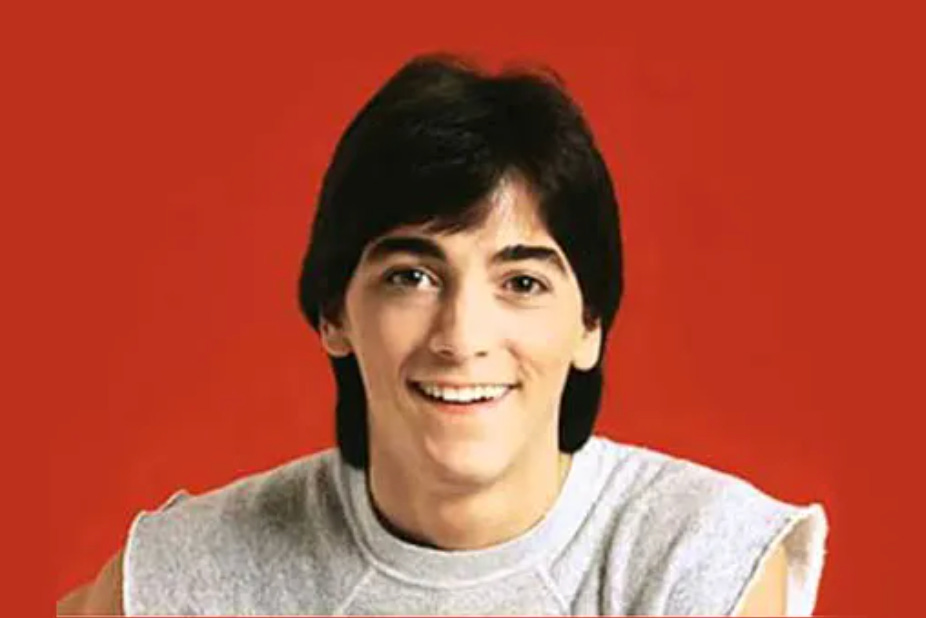

Scott Rogowsky

Nordic Mythology

Prof. Morten Warmind

May 5th, 2006

The Parodic Edda

Much is known of the pre-Christian beliefs held by the peoples who settled Scandinavia in the early centuries AD through various written transcriptions of Norse histories and sagas that have survived the many generations. The canon of Nordic Mythology is rich with the tales of Odin, the Norse god of wisdom and war; his wife Frigg and sons Thor and Balder; the love goddess Freyja and her brother Freyr; Loki, the god of mischief, and his wolfen son Fenrir.

But a recent discovery has brought to light the mythologies of many forgotten and previously unknown Nordic deities. In the fall of 2005, the demolition of a Frederiksberg townhouse was stayed when a shoebox containing a collection of Penthouse magazines from the early 1990s and a book of ancient skaldic poetry and saga was discovered in a crawlspace under the basement stairs.

The manual of poetics is believed to have been authored by Snoring Stutterson, the renowned Icelandic scribe and historian more famous for having suffered from narcolepsy and various speech impediments than for his oft-piddling mythography. The codex, dubbed The Pathetic Edda, is composed of three sections: the first describes the saga of Scott Baiowulf’s journey from his native Iceland across the North Sea to Sjælland to perform in the very first Roskilde Music Festival; the second is Hrbek’s Poem that relates the story of the brave Hrbek and his quest for the great northern white ash tree, Hillerich; the third part, written on college-ruled loose leaf paper and messily stapled to the other two, is a list of Kurt Russell movies in which the actor can be seen sporting a tank top and mullet.

Radiocarbon testing date the first two manuscripts, well-preserved on their original calf vellum, to the early twelfth century, while paleographers using Nintendochronolgy, a controversial but more precise method of scientific dating, have determined that the addendum was written by a 17 year-old boy who had stayed home from school to beat The Legend of Zelda sometime during late 1980s, making it a genuine relic of the Germanic Aluminum Age. Contemporary scholars further researching the document also maintain that the boy was briefly employed at his neighborhood 7-Eleven and frequently lied about the status of his virginity.

In recent months, professors at the University of Copenhagen have completed the arduous task of translating The Pathetic Edda from its original Norse into the humorous Pig Norse, and then into Tamil, a Dravidian language popular among native Sri Lankans. While it is estimated that an official English version will not be available for another three to four years, an Ohio-based amateur historian calling himself “Shwaggy Steve” has published an incipient interpretation of the Edda on his web log The Stoned Rosetta, having translated the manuscript using AltaVista’s Babel Fish during commercial breaks of a Quantum Leap marathon on the Sci-Fi Channel.

Steve’s work has been copy and pasted here for the purpose of this graded writing assignment without his permission, but with full confidence that he will never find out.

Baiowulf

Here we begin with a riddle asked of the great Odin before he was allowed to go sledding: “What is the difference between a ewe with a headache and a mallard with a cold?” One’s a sick duck… well I forgot the rest, but allow me to tell you the story of King Philbin and The Family Baiowulf.

Philbin ruled over a small parcel of land in the birch forests of Iceland whose location next to a slaughterhouse had greatly reduced the property’s value on the secondary market. In a clearing he had built a cottage in which he lived with his wife Guri and his three sons, Jimmy, Esteban, and Scott. Philbin was at one time a revered king, adored by his subjects/neighbors, the Jorgensens. But he had grown gray with age and increasingly fond of the bottle, and frequent attacks of delirium tremens had rendered his sovereign reign unstable.

Guri was a woman of great strength and interpersonal skills, and her hatred of rodentia had led her to establish a successful exterminator and pest control employed on occasion by the gods themselves. It is said that her thorough handling of a carpenter ant infestation garnered much praise from the noble Bragi in the form of his celebrated poem-ballad “Only the Best (Can Locate the Nest).”

It is said that Jimmy and Esteban were young men of good stock and had gone into real estate business together, developing condos in Valhalla to meet the burgeoning demands of slain warriors entering Odin’s hall. Guri was very proud of these two sons and their profiteering, and she would often prepare for them morning dew cakes, malted meadshakes, and other sweet treats as a show of her affection. But of her youngest Scott she felt only shame and served only reindeer hoof.

As a young child, Scott was given every opportunity to become a bold warrior and was expected to succeed his father on the throne. He was taught to forge his own weapons, trained in the ancestral ways of swordsmanship, and he even spent a summer at Master Egil’s All-Star Archery Camp for Lil’ Bowmen to further hone his craft and experiment with soft drugs. But as he grew into adolescence, Scott, who was called by the family name Baiowulf (and also answered to “Iceman”), had no interest in the warrior profession. He appreciated the arts and excelled in musicianship. In that way, he took after his uncle Dobro the Fretless, the most celebrated dulcimer craftsmen in all of Midgard. It was Dobro who taught Baiowulf the intricacies of playing the psaltery and had introduced the talented youth to Reykjavik’s vibrant underground pagan rock scene.

Now there is this to tell: Baiowulf was sitting on a stump, composing a pleasant tune on his bone whistle, when he heard a rustling in the forest. He gave his whistle a rest, stood up, and listened for the sound to repeat. Once again, he heard the crunching of twigs and saw movement in the trees. A short, bearded old man appeared at the edge of the clearing, dressed in tattered garments and clutching a scroll. His eyes opened wide as he hurried towards Baiowulf and spoke:

“Young man, I am called Sisqó, son of Korg and descendent of Roland, King of the Synths. I am exceedingly skilled in the bardic arts, and I have written many of the songs the Æsir fancy today. Alas, I hold here in my hand the lyrics to the greatest song ever written, a song that will surely captivate all the gods and goddesses of the Asgard in simultaneous head nodding. I call it Diphthong Song, but it has remained incomplete and has never been sung, for I have yet to find a suitable melody to match my words. Lo these forty years I have wandered the realms of mortals far and wide across woodlands and great plains, listening for just the right tune to complete my masterpiece. Today, the wind carried the most wonderful whistling to my ears, and I stand before you now, having followed the sound to you and your bone instrument. You must accept these lyrics and perform the song at the music festival in Roskilde that is scheduled for next fortnight to mark the vernal equinox.”

With that, the noble bard extended the tightly bound scroll to Baiowulf and continued: “I have endured countless ailments and suffered tremendous fatigue in my many years of wandering, but I remained strong to ward off the temptress Hel until I had found the perfect suitor for my poem. Now that I have heard your melodic strains, I can entrust to you my words and surrender my feeble body to what lies beneath.” And before Baiowulf could even express a gesture of gratitude, Sisqó collapsed to the ground and released his final breath.

The startled Baiowulf ran in search of his uncle Dobro who would surely know what to do with the song and how to economically dispose of a dead body. Dobro was in his workshop, perfecting a new hammer-assisted dulcimer, when Baiowulf excitedly entered with the news: “An old man came to me in the wood, having been wooed by the sweet melodies I have composed on my bone whistle. He called himself Sisqó and claimed to be a bard well renowned among the Æsir. He handed me this scroll on which are printed the lyrics to the Diphthong Song, the greatest song in the world. With his dying breath, he summoned me to perform the song at Roskilde.”

Dobro stood at attention: “Sisqó, you say, was the man who came before you. Son of Korg? Descendent of Roland? My nephew, Sisqó is my father Moog’s brother, your great-uncle. Moog would always speak of him with much fondness – he had run away from home at an early age, but was blessed with incredible talent as a songsmith. No one could create an infectious party beat like Sisqó, and his music has made the gods well-pleased. We must go to Roskilde to perform this song and continue our family legacy.”

Baiowulf went to his mother, who had just come back from Asgard after ridding Tyr’s wine cellar of a roof rat infestation, and told her of his plans. Guri never had much time for her youngest son or held any interest in his “mindless musical ramblings,” as she called them. “You put down your sword so you can fiddle around on your whistles and whistle around on your fiddles, and now you want to sail off to Denmark for a music festival? Go to Roskilde; get out of my house with this nonsense, and just go. If you don’t come back, I will not consider it a loss too great.”

Baiowulf tried to explain the importance of the song and his connection to Sisqó, but his mother’s harsh words had stung, and he sought his father for redemption. King Philbin had been steady with the mead that day and was experiencing severe macropsia when his son approached with news of his impending travels. His father’s state necessitated that Baiowulf stand fifteen feet away as he said: “I’m leaving for Roskilde. There is a music festival that I must attend, with Sisqó’s song in hand, to spread the divine music that rests deep in my soul. It is called Diphthong Song, and it is the greatest song in the world.”

But the drunk and visually-impaired king could only babble incoherently in response. The dejected Baiowulf then left his broken home with a packed bag of his favorite tunics and his trusty whistle. When he met with his uncle at harbor, he was his own man.

It is now told the two men left comfortable Iceland and traveled by small craft across the treacherous seas, subsisting on the generosity of Njordbær, the vegan god of seafood, who provided daily rations of his famous chopped sea salad. It was a mixture of sea lettuce, sea cucumber, and sea avocado with Njordbær’s special Baltic vinaigrette made from scratch of pressed kelp and cormorant droppings.

Though generous, the portions were rather unpalatable. Not ones to complain, especially at the charity of a good-meaning god, Dobro and the young musician managed to stomach the helpings. But there were many times during the trip when Baiowulf quietly cursed his bad luck for drawing the auspices of the vegan god, remembering that the Jorgensens were treated to the finest shrimps and herrings during their transatlantic passage on a family vacation several years prior.

On the third day of their second week of seafaring, the two men reached the shores of Denmark, landing near Hundested at the mouth of the Isefjord. Exhausted and quite sickened from the Baltic vinaigrette, Dobro and Baiowulf were visited by Gnocchi, Loki’s half-Italian half-brother and god of pasta dumplings. He spoke to them: “I have watched you journey from Iceland across the treacherous seas, eating Njordbær’s well-intentioned but woefully unpleasant provisions. Please forgive him and his veganism; we believe he’s just going through a phase. Allow me to treat you with a feast of potato-filled pasta lumps, on behalf of the Vanir.”

Gnocchi stepped aside and revealed a table set for two in the shelter of a large ash tree, and with a flutter of his slate blue, cotton velvet cloak that he wore to add a sense of mystery and drama to his life, there appeared on the table a bucket of pasta dumplings. “It is a veritable never ending pasta bowl,” quipped Dobro, and the tired travelers ate to their hearts content as Gnocchi sat nearby, watching intently and breathing heavily, occasionally murmuring under his breath, “Yes, just like that. Eat it, eat it all up.”

Now is the time to tell that Baiowulf and his uncle, weary of the waterways, journeyed on foot the rest of the distance to Roskilde. They knew they were close when they came upon the pedestrian traffic that had accumulated for the start of the festival. The event promoters had advertised all across Denmark and Sweden, and over 200,000 people were expected for the weekend to celebrate music, culture, and humanism. Ninety-six bands and bards were scheduled to perform in eight music tents over the three days, among them the acoustic folk-duo Saga Genesis, the alternative noise rockers Rage Against the Ragnorak, and the celebrated Odin’s Dirty Bastards, a string quintet featuring five illegitimate sons of the All-Father.

Baiowulf fought his way to the front, his uncle following close behind. They reached the main stage as the headliner Signy Pop and The She-Wolves were in the middle of sound-checking. Baiowulf knew this was the right time, and he climbed up on stage clutching the scroll and this bone whistle. Dobro set up beside his nephew with his hammered dulcimer tuned to the key of rock, and began hammering the intro lick. Baiowulf took a deep breath, unfurled the parchment, and began to sing. The audience quieted and turned to the stage as if drawn by a divine power. Baiowulf then took out his whistle and took control of the melody, a sound so sweet as it met the ears of everyone in attendance.

The music soared skyward and reached the Asgard where the assembly of gods put down their Sudoku books and froze in rapt attention. The ethereal music had mesmerized the whole world at once. And then, a flash of bright light illuminated the night sky and the crowd broke into a frenetic dance. The driving beat and catchy hooks of the Diphthong Song had the stars themselves undulating to the rhythmic pulse. Baiowulf blew on his whistle, Dobro plucked his strings, and some men say the spirit of Sisqó hovered above the stage and assumed lead vocals.

The song concluded and Baiowulf received a seventeen-day standing ovation. The rest of the festival was cancelled, as there was no need for any more music. Diphthong Song had captivated a continent, and Baiowulf went on to become a celebrated recording artist and master of the bardic arts, and after him his songs have been handed down from one man to another.

Hrbek’s Poem

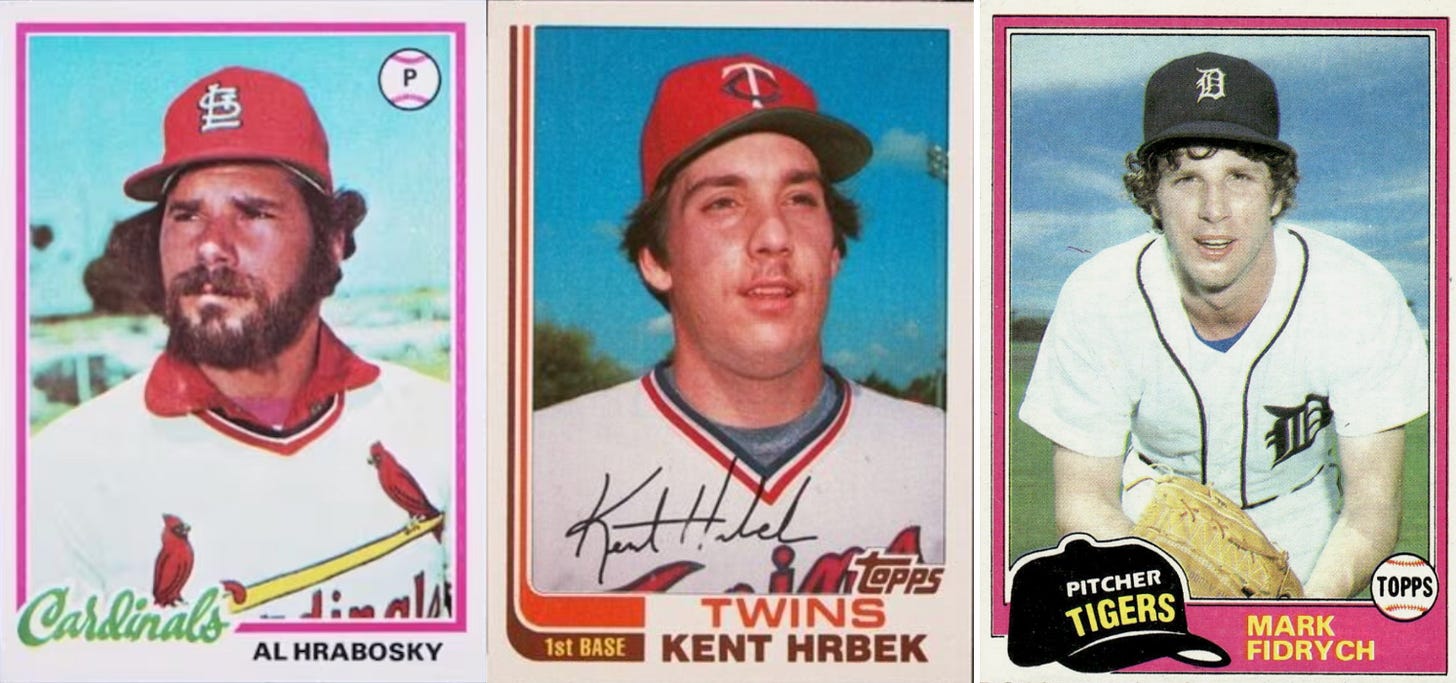

Hrbek’s Poem (Hrbeskvida) is well-preserved but rather poorly written, an unfortunate hallmark of Stutterson’s work. The sated gods wished to be entertained with a home run derby between Thor and Hrbek, the greatest batsman in Midgard. Hrbek realized he wouldn’t stand a chance against Thor and his mighty hammer unless he could fashion a bat out of the trunk of great northern white ash tree, Hillerich. He goes to the Utgard ash forest where Hillerich stands, protected by Hrabosky the Reliever, and along the way meets Fidrych (The Bird) who agrees to fly Hrbek to Hrabosky’s bullpen.

Like most encounters between batsman and reliever, the adventure is all fun and games until someone gets hit by a pitch. In this case, it is Hrabosky who suffers a debilitating strike at the hands of Fidrych who took revenge for his banishment from the rotation. In the end, Hrbek is declared the victor at the discretion of the gods whose collective attention deficit has diverted their concentration back to logic-based, number-placement puzzles.

1 Once, the fastidious gods feasted on lox and bagels,1

they demanded entertainment of brutish display;

they sought a derby to determine the greatest swing,

they found that Odin’s son and Hrbek made a desirable

match.2 The Twin Cities-dweller propped up, his cheery nature2

turning to that of concern as he eyed Mjolnir,

Hlorridi grinned knowingly and looked into his eyes:

‘You are going to need Hillerich’s trunk to claim victory.’33 The trashful talk did not find Hrbek well;

he began to consider the joke in a serious light;

he announced his intention to call the bluff and make path,

‘towards the great ash forest protected by the Relievers.’44 Herbie dismissed the charity of his friends;

the gallant Gaetti offered his club,

the burly Brunansky hoisted his weighty stick in gift,

even the mighty Killebrew stepped forward from the famous

hall to extend his own silver slugger.5 The defiant one said his farewells and marched east,

his fearlessness perceived as recklessness by the gods;

only upon nightfall did the great outdoorsman feel regret,5

‘The fireballer stands guard and awaits my arrival.’66 The lad was stirred from his sleep by a giant egret,7

Fidrych, the brave Reliever who had lost favor with the

father of Fu;8

he wished to enact revenge and found a partner in the eager

Herbie.7 ‘Intrepid traveler, I will lead you to Hrabosky’s pen

where you can secure a branch from the great ash tree.

I wish to face the Mad Contrarian once again;

I will meet his fastball with a blazing speed pitch

of my own.’8 The thick-armed playmate of Puckett held to The Bird9

as his broad wings flapped and flew the rest of the way.9 Hirsute, sinister-handed Hrabosky

came late back from grooming the mound.

He went into his bull’s pen to gather stock for his supper;

nobody made a finer ox-tail soup.10 ‘Greetings, Hrabosky, I have come to your pen to tell you

of a batsman in need of wood,

the root-stem of Bradsby’s better half is what he requires10

to defeat Sif’s husband and earn respect from the Æsir.11 See where he hides behind the manure pile;

I overheard his plans for cutting down great Hillerich

whilst you tended to your bulls.’12 Steam did the pile at the Reliever’s gaze,

and the terrible smell, an olfactory nightmare,

roused Herbie from his spot.13 ‘You come to the Great Ash Forest

for my precious wood, but you are mistaken to believe

you can fell my trees without provoking my favor.

I say, follow me to the mound.’14 Forward they went, and the mustachioed giant

turned his gaze on his brawny intruder.

His mind didn’t speak encouragingly to him,

when he saw

the one who had initiated the T-Rex Tag.1115 Fidrych walked behind Hrbek and Hrabosky,

until they reached the manicured mound

where the Mad Contrarian said no man could

hack at Hillerich if he could not lift the rosin bag.16 With that, the brave, royal cardinal grabbed

the bag in a huff,12

jerked it skywards and violently hurled it down at Herbie,

who managed to dive wayside to escape

the cloud of powder.17 The oft-injured Hrbek stood and dusted himself,

approached the mound with newfound vigor;

the rosin bag he tried to lift but buckled under,

again he grabbed at it whole and failed after a struggle.18 Until the friendly Bird told him

some birdly advice which he knew:

‘Cut the bag and bleed the rosin, the heavy element;

Hrabosky’s challenge is as flawed as his delivery.19 The strong man, hunter of ducks, slit the bag and

spilled its contents;

the emptied purse high above his head

a show of cunning to enrage the Contrarian,

fuming red with the madness of a hundred Martins.1320 ‘My challenge you met with chicanery,

and my prized rosin you have rendered unworkable;

never again will it dry my sweaty palms

or inspire my entertaining mound rituals.21 You must pay for your transgressions;

my fast ball will send you straight to the Hel’s pit.’22 The thickly bearded Reliever wound up to deliver his blow,

but the unorthodox Fidrych intervened before the release;

a wicked slider sent Hrabosky to the ground,

sprawled and shaken.23 Hrbek worked quickly and wrapped his thick arms

around Hillerich’s sturdy base,

with bent knees he brought all his divine power to bear;

each tug steadily loosened the unyielding soil

until the whole of the great tree had been uprooted.24 Hillerch in hand and his wonder bat secure,

Herbie had not gone far from the pen

when the burly batsman looked once behind him;

he saw the fiery southpaw approaching with flared nostril

admirably framed by bushy mustache.25 He turned and swung the mighty ash, eager for slaying,

and contact was made on the sweet spot indeed;

the giant hurdled through the air until his bones met

with Ymir’s in a bloody mess on the mountain.26 The satisfied Hrbek came to the assembly of the gods,

dragging behind him the Reliever’s sacred ash;

the father of Modi knew well from the red-stained wood

that the derby was well under way.27 But before Thor could take any cuts of his own,

the impulsive gods had already grown weary

of the contest;

Hrbek was declared the winner,

and the gods returned to their Sudoku.

lox and bagels: traditional Sunday morning meal of the Æsir; suggests a brunch time scene

Twin Cities: refers to Hrbek’s place of birth, likely two cities divided by a river

Hillerich: Great Ash Tree, prized for its wood of the lowest grain count per square inch

Relievers: The race of eccentric giants assigned to watch over Hillerich and the Great Ash Forest. Hrabosky, The Mad Contrarian, was considered the leader of the Relievers

the great outdoorsman: Hrbek, who was celebrated for his hunting and fishing skills

Fireballer: Hrabosky, so called for the iron ball he throws with blistering speed

giant egret: Fidrych, also known as The Bird

Fu: Hrabosky, so called for his style of mustache

playmate of Puckett: Puckett was a well-known batsman, ‘playmate of Puckett’ is a kenning for ‘batsman.’

Bradsby’s better half: Hillerich

T-Rex Tag: nickname given to Hrbek’s infamous 1991 put out of Ron Gant in Game 2 of the World Series

brave, royal cardinal: another kenning for Hrabosky, referring to his affiliations

a hundred Martins: Martin was legend for his incendiary feuds with the powerful Steinbrenner.