The artist was taken into custody on the morning of July 4, 2012, detained by Burbank police following a brief foot chase after crashing a reportedly stolen vehicle into a light pole.

On December 16, 2013, a jury was unable to reach a verdict on charges of first-degree burglary and grand theft.

On June 16, 2014, a different jury found him guilty.

On September 26, 2014, a judge sentenced him to 17 years in California state prison.

On November 26, 2024, the artist was released.

The artist is Gerjuan “Ge-Cue” Harmon. He was born an artist, in Detroit, and despite a fractured childhood in South Central LA that left him orphaned at three years old and a challenged adolescence in Burbank that saw him shuttling between foster care and juvie — even despite serving 12.5 of those 17 years — he never stopped being an artist.

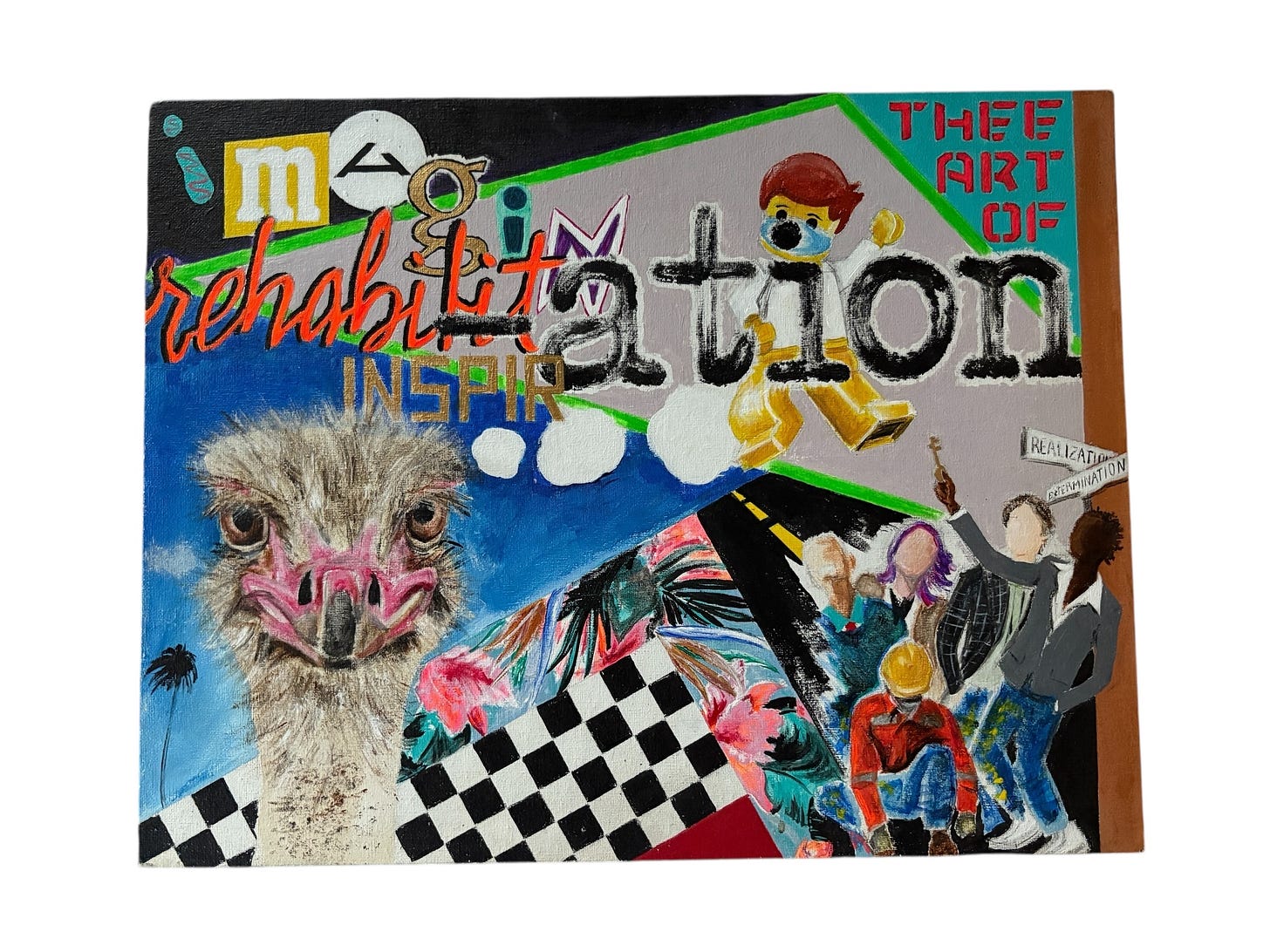

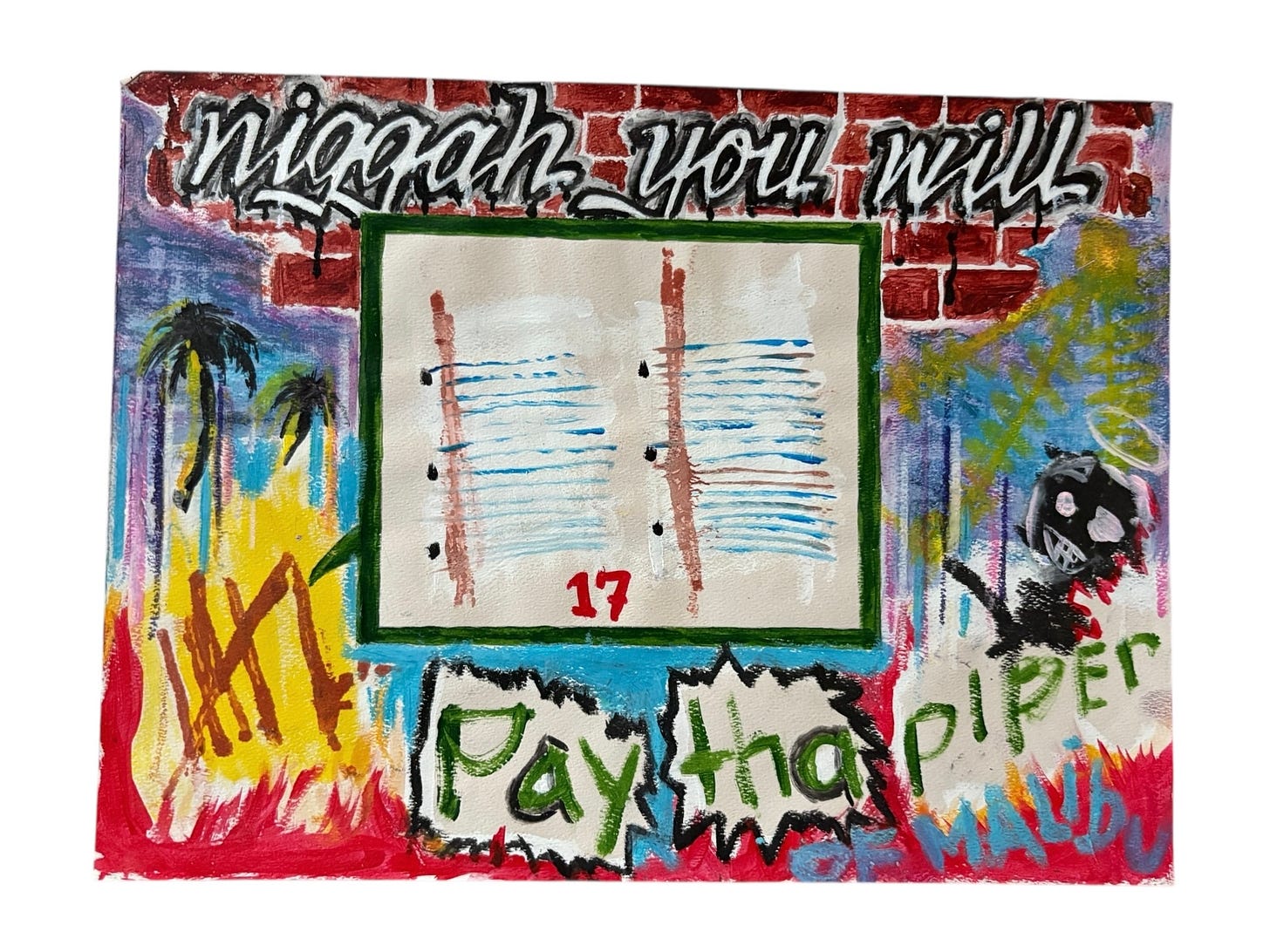

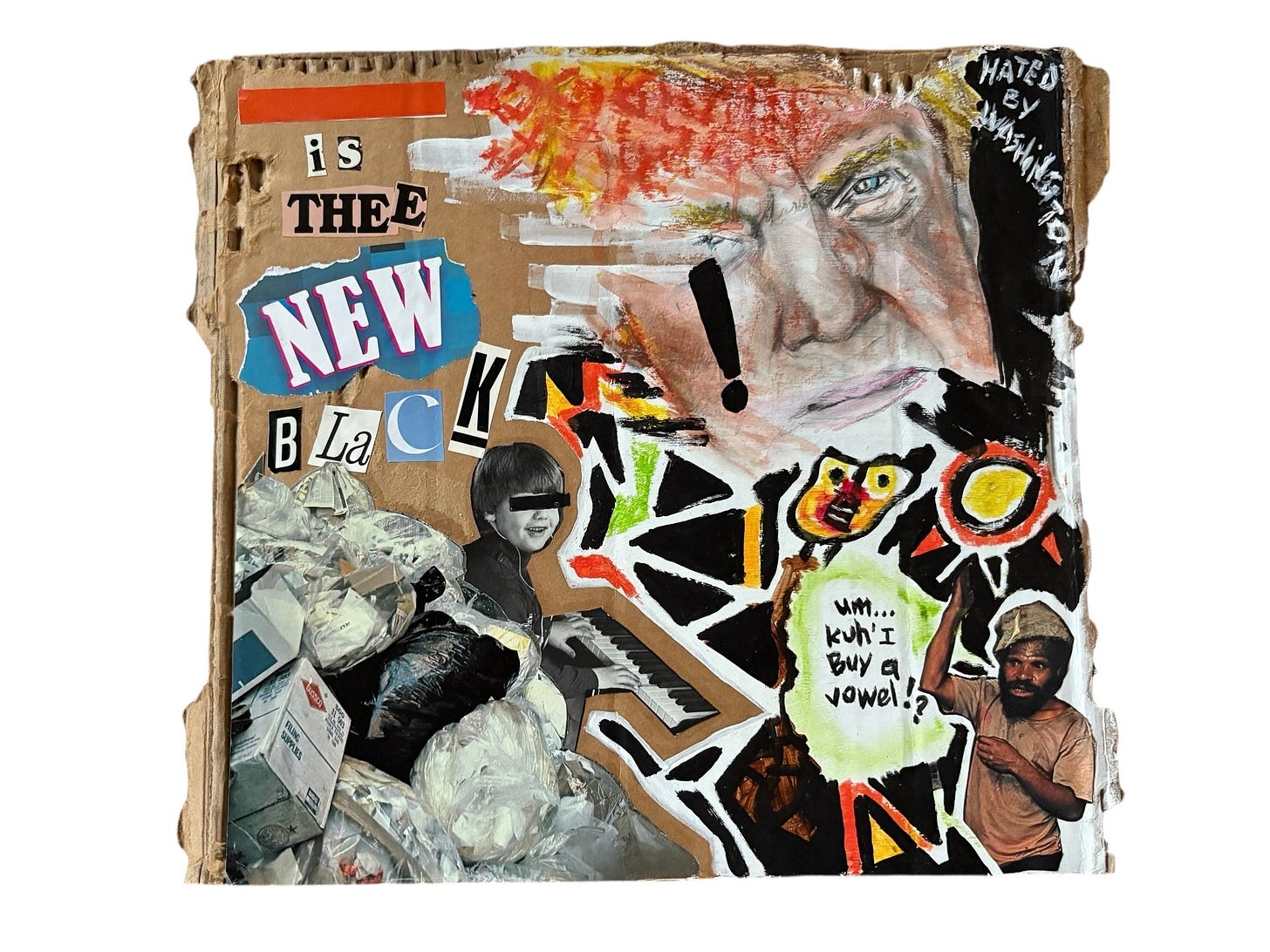

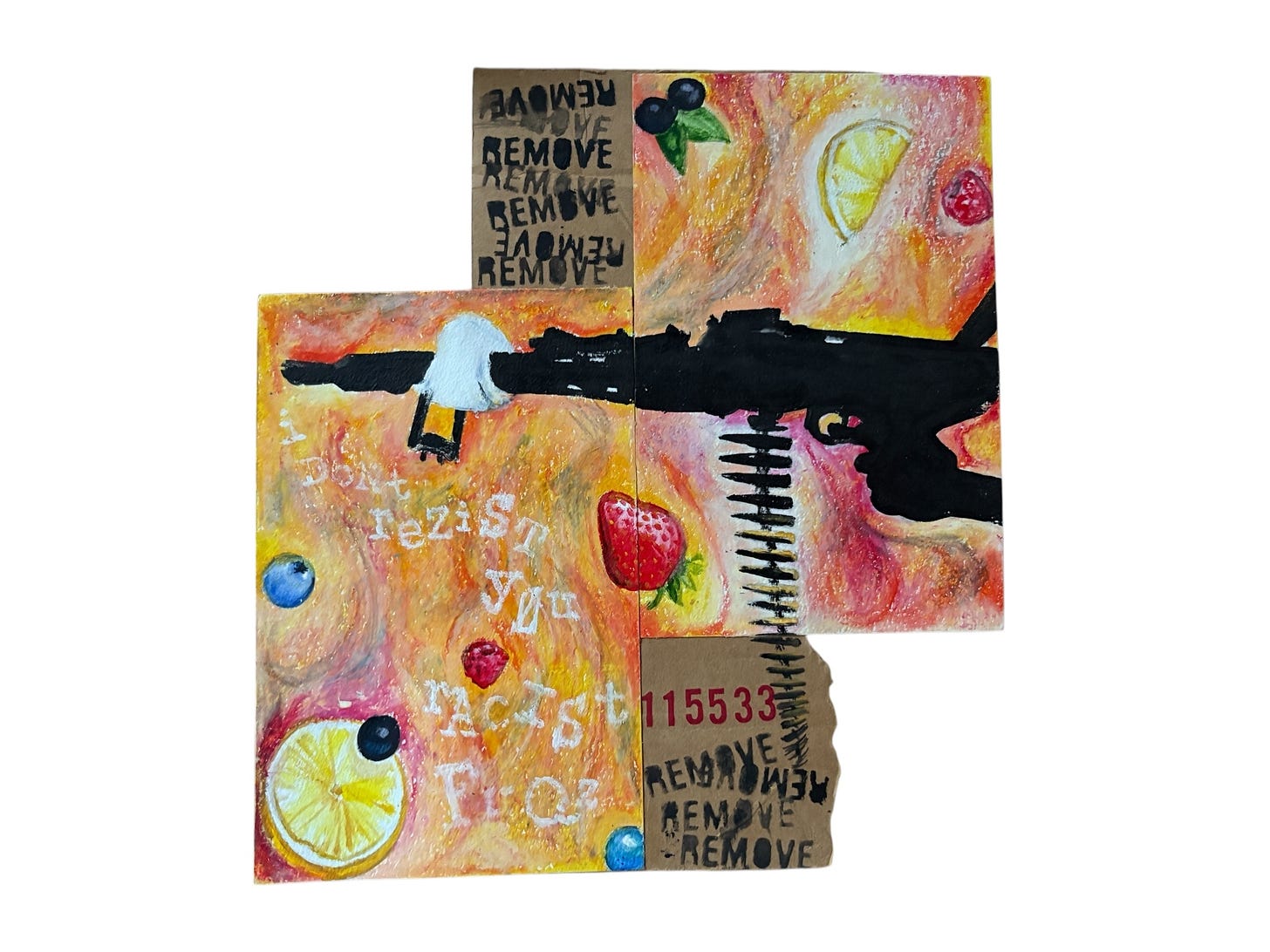

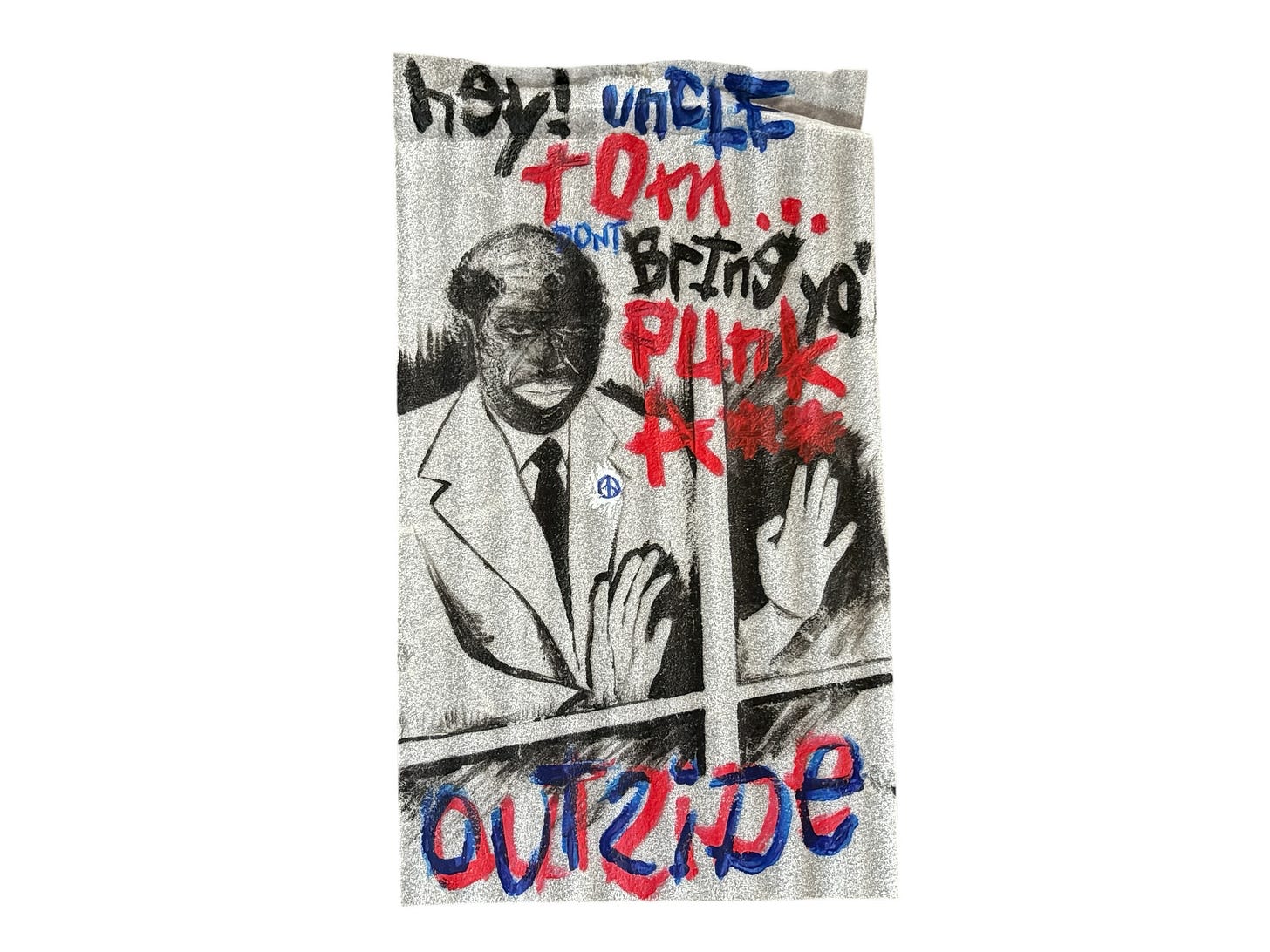

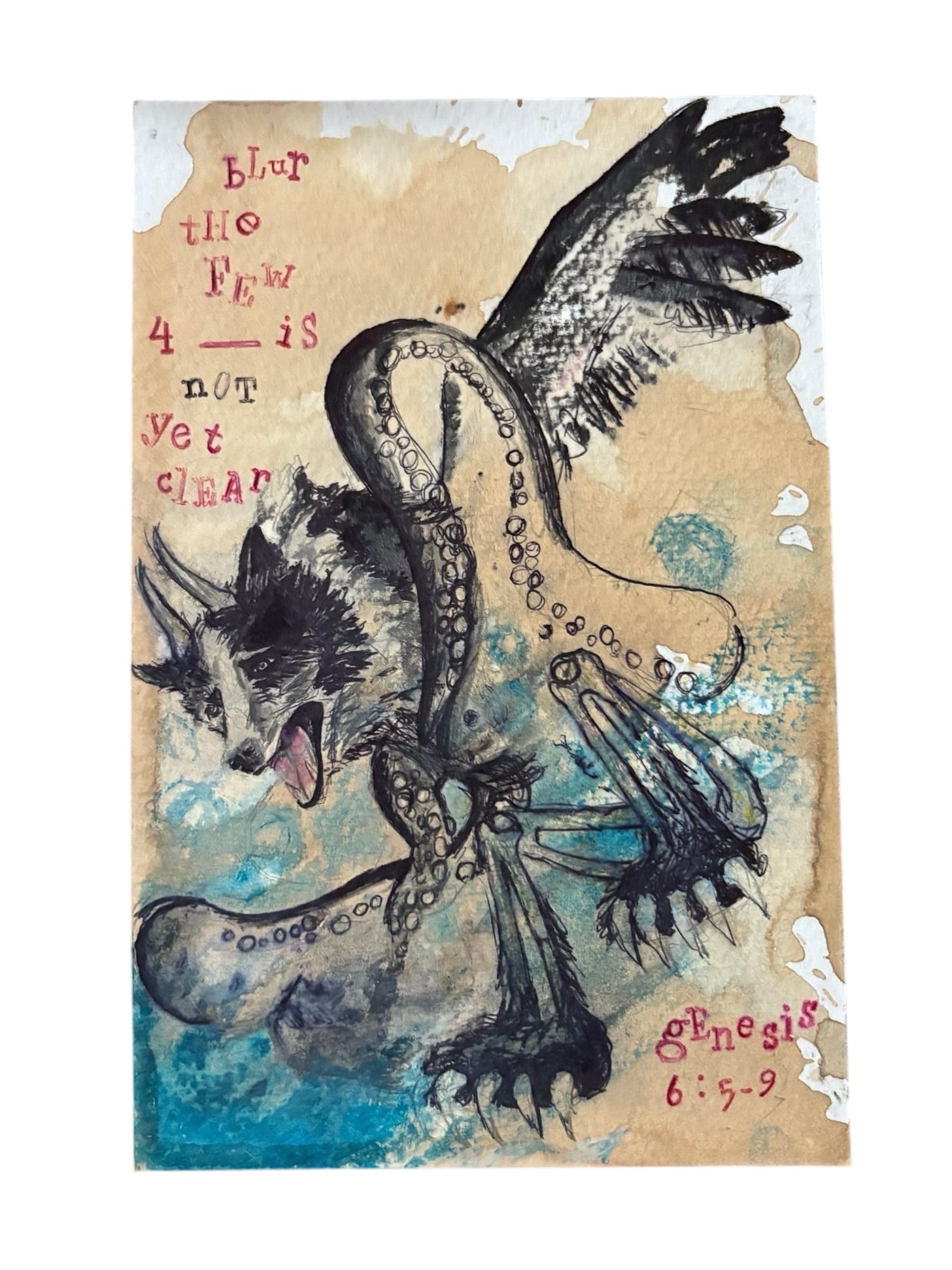

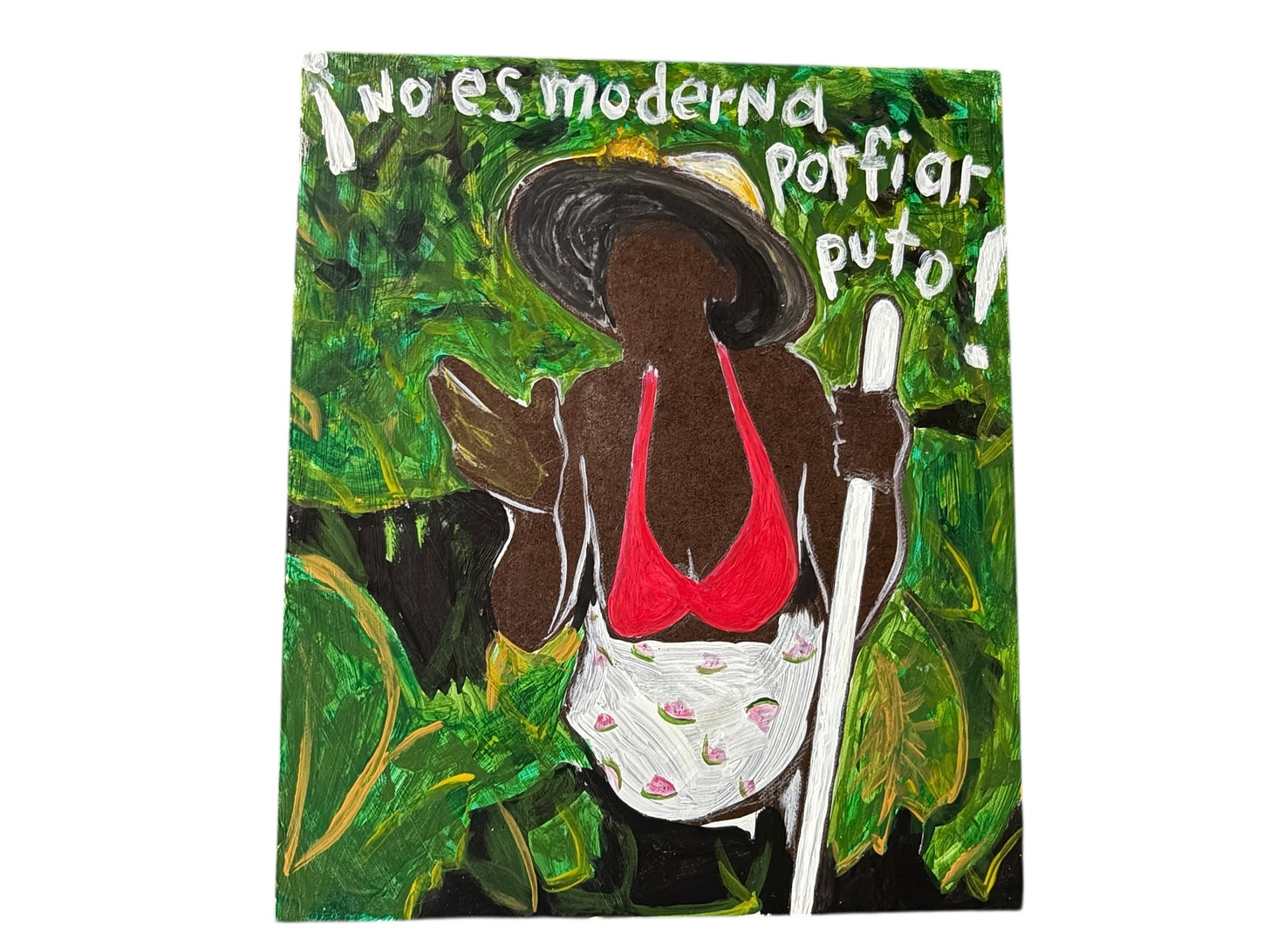

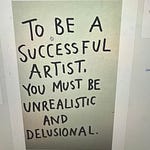

In fact, it was while in prison, after recharging his creative energies and reconnecting with his bohemian spirit, that he experienced his most prolific artistic streak — yielding dozens of works using improvised tools and “found” canvases and materials, many considered contraband by the COs who monitored his every move (but looked the other way once his rare talent was recognized).

Gerjuan sketched, etched, painted, sculpted, collaged, imagined, manifested. He was commissioned to design graphical informational posters for fellow inmates and paint murals for the yard. He sent his work out into the world, cold-mailing his precious art to entertainers, creative directors, entrepreneurs, professors — anyone whose image flicked across the television in his cell or the projector of his mind that he admired and felt inspired to make a connection.

I was one such person, who in December 2023 received a mysterious package in the mail with a return address label from “California Men’s Colony — San Luis Obispo,” containing an impressively decorated wooden plank and a three-page, hand-written letter from the artist.

His unsolicited outreach and gifting of a piece of his very soul touched me at the core of my own, sparking a correspondence and subsequent friendship over the past year. Recently, I had the privilege of visiting Gerjuan at his home in Toluca Lake — not far from the streets of his troubled youth and the scene of his life-changing arrest — where he’s balancing civilian reintegration after more than a decade of incarceration with the full-time rigors of film school as a 41-year-old first-year cinematography student.

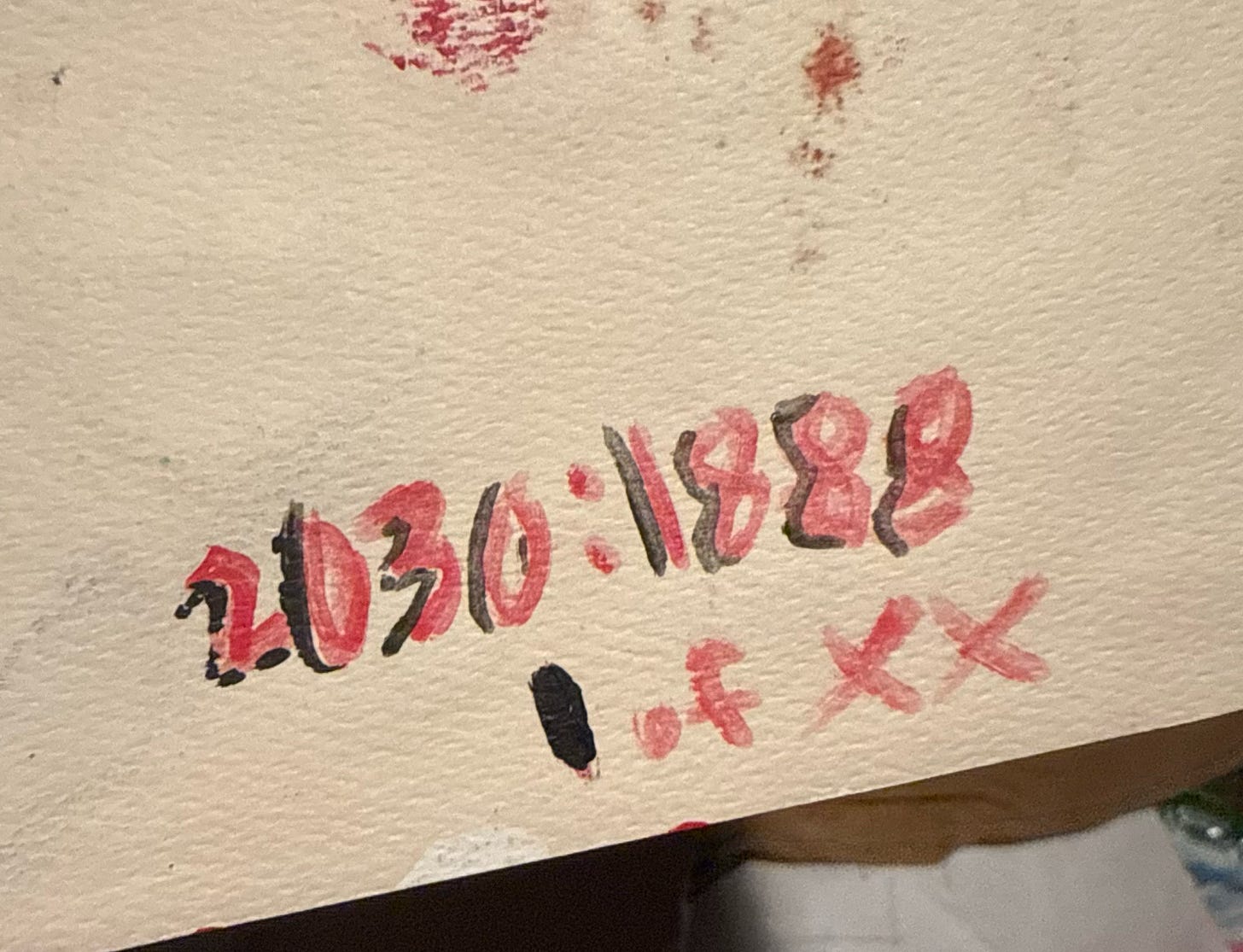

Gerjuan proudly arranged his portfolio on his bed for me to admire: dozens of pieces he had managed to send to friends and family on the outside for safekeeping, each a conduit for vicarious liberation while his body remained in bondage. One particular series caught my attention due to its cryptic numerical notations on the back. Gerjuan explained:

I was teaching art at the prison, and there was a lot of debate going on — I don’t remember if it was just between us at the facility or the art world in general — about what constitutes “Black Art.” My take was: just because I’m Black doesn’t mean I have to portray Black people in every one of my paintings. If I remade Da Vinci’s The Last Supper with Armenians speaking Chinese, it’s still Black Art, because it was made by Black hands.

It was also around the time of the 30th anniversary of Basquiat’s death [August 12, 2018]. So to honor him and his legacy, I committed to making a new piece of art every day for 20 straight days. I called the series 2030:1888 — 20 for the days, 30 for the years since Basquiat passed, ‘18 and ‘88 for the 30 years in between [1988-2018].

This series is just a small sampling of the many “miracles” Gerjuan produced and salvaged — works that, by all rights, should never have made it beyond his prison walls. And yet, here they are: resting in a spartan Toluca Lake bedroom, quietly awaiting their inevitable recognition by horn-rimmed critics and flowing-linened gallerists of the international Art World — once his full story is finally told and shared.

In the meantime, Gerjuan continues to struggle. The film academy he’s been attending since January has been rinsing him for every nickel he’s got — and he hasn’t got much. Getting by on Dollar Tree groceries, city buses, and the kindness of friends and family (albeit, kindness that’s straining under the weight of his dire straits), he’s now relying on the GoFundMe we launched this month, and the sale of his precious art to make ends meet and fund his capstone film project. Just this past week, he was forced to cough up another $500 for an insurance certificate at the eleventh hour of his final shoot — the latest in the string of hidden costs that have hampered his creativity, dampened his spirit, and in his darkest moments, tested his sanity.

Even with you giving me money, financial aid giving me money, I took out a loan, and I still can’t cover it all. Those [expletives] at the school STILL got their hand out? I don’t understand. What is there that I DON’T have to pay extra for? $25 here. $25 there. And then they hit you back, “Oh you didn’t fill this form out” — that’s another $45. And the school doesn’t cover any of it. That’s where the frustration lies, and the more I get my mind on that, the less enthused I get about it all. They got me in a vice grip.

The art speaks for itself. His story speaks for itself. If either moves you, please consider supporting Gerjuan here. If you’d like to purchase any of his art or request more information about any of the pieces in the video, please email the artist directly.

New to this story? Catch up with the first post and Episode 1 of our podcast RELEASE: Life Beyond Bars. Follow Gerjuan on Instagram @crushederasers.