039 - My Baby Mama Trauma

Exploring the trauma I experienced as a baby born to a mother with Multiple Sclerosis

My mom turned 75 today.

TOO SOON???

Tobi Ann Steinberg was born on April 8, 1950 (the math checks out) to Sydney and Elsie (née Regenstreif) in Norwalk, CT, becoming younger sister to Jeffrey who arrived three years earlier.

By all accounts, young Tobes was the perfect little girl with blondish bangs, always got good grades, never got in trouble, was helpful around the house and popular with her many friends. Jeff considered her a pain-in-the-ass for constantly making shit up to get him in trouble and ratting him out for the slightest misdeed, but he appreciated her compliance in keeping his biggest transgressions — like the time he stole the family sedan for a late night joyride — a secret between siblings.

So what if it required a coercive threatening of her life?

Tobi developed a bookish personality and a social consciousness in her teen years, while occasionally gracing the local ice rink or tennis court. After graduating from Norwalk High with honors, she took her talents to Glenside, Pennsylvania to attend what is now called Arcadia University, but what was then a regionally prestigious, all-girls, liberal arts school known as Beaver College — most notable for existing at a time before vaginal slang.

I once asked my mom about the other colleges she applied to. She told me she got into Snapper State and Pink Taco Polytechnic, but was waitlisted at SUNY-Cuntchester and rejected by UMASS-Twatsboro.

Tobi’s political activism took her from boycotting grapes at the Steinberg dinner table to turning her back on her commencement speaker George H.W. Bush. Her first move out of college was cross-country to California where she joined the staff of George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign — an effort that ultimately proved unsuccessful. One of her most prized possessions is a hand-written letter she received from McGovern’s running mate Sargent Shriver in the wake of their historic, landslide loss to Nixon and Agnew, assuring Tobi it was not entirely her fault.

Riding the political winds back east to the nation’s capital, she settled down in DC where she received her JD from GW, taking law classes at night while supporting herself with her day job as Betty Ford’s personal bartender.

During the last days of disco, Tobi agreed to be set up on a blind date with another thirty-something Jewish lawyer from the northeast named Alan Dershowitz. Tobi waited for him at L’Auberge Chez Francois for two hours, but Alan never showed. Sobbing at the bar, she was approached by a tall, handsome stranger with brown shoes that violently clashed with his milky blue eyes.

He introduced himself as “Jewish lawyer Marty Rogowsky,” explained that he had also been stood up by a blind date (Anita Hill), and offered to buy her a club soda with a splash of cranberry juice, extra ice.

One year later, they were married. Two years after that, I was born. Two years after that, my sister Rayna was born. Four and a half years after that, Nirvana’s Nevermind was released to worldwide acclaim, bringing the alternative grunge scene to the mainstream and redefining rock music for a new generation.

I don’t need to tell you how that story ends.

But there’s another storyline running through Tobi’s life, a story that begins during her semester abroad in swinging London as a 21-year-old college junior with a trendy smoking habit. One night outside of a pub with friends Twiggy and George Harrison, her fingers inexplicably went numb and she dropped her fag. Confused and concerned, she urgently sought a medical evaluation, which led to a diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis.

Truthfully, she was initially told she had Singular Sclerosis, but being the savvy consumer she is, Tobi couldn’t resist using a two-for-one coupon.

My mom has carried her condition close to her vest for the past fifty-plus years with a steely resolve and a quiet dignity, through law school and her young professional career, through her marriage and motherhood. MS is a progressive disease that slowly degrades the nerve pathways of the body resulting in impaired motor functions. Walking is usually the first to be affected. Bladder control next. Vision blurs, hearing fades, swallowing becomes a chore. Chronic fatigue sets in. Handwriting becomes difficult, and then impossible. One day you park the car in the garage and find yourself too tired to get out from behind the wheel, and you never drive again.

The people in her orbit love and respect Tobi for her strength and resilience in the face of her malady, sure, but more so for her emotional intelligence, her sense of humor, and her world-class goss served hot n’ fresh on the reg. They know she has never let herself be defined by her disease and rarely calls attention to it, unless it’s in service of working a few shekels out of them in her year-end appeal for the MS Society — a leading research-funding nonprofit for which she, in her decades-long affiliation, has personally raised well north of one million dollars.

I hope to never know what it’s like to stand in my mom’s uncomfortably tight shoes with her edema-afflicted feet. I hope to never know the constant feeling of heaviness, the all-encompassing physical and emotional exhaust, and the persistent bouts of mysterious aches and pains that has necessitated 40 years of afternoon naps in a relentless quest for relief. I hope to never experience losing my balance and falling in public, in front of my kids, and then having to come to grips with a gradually increasing reliance on what starts as a cane, then becomes a walker, then upgrades to a rolling walker, before graduating to a wheelchair for outside and an electric scooter in the home.

From what I’ve seen up close, living with MS is none too fun.

Neither is living with a mom who is living with MS.

As children of a chronically ill parent, my sister and I grew up very differently from our classmates. We could neither enjoy the pleasures of playing jump rope or kickball with our mom, nor could we avoid the sorrows of seeing her hooked up to a frightening mess of tubes and terrible beeping machines in the hospital, or witnessing her wince her way through agonizing nightly therapeutic injections administered by our dad at home.

I grew up with a compartmentalized awareness of my mother’s situation, allowing it to buffer in the background while I focused on other tasks. With her, I baked brownies and made latkes, went summer camp and back-to-school shopping, sang along to “Golden Oldies” on the car radio — simple joys that her disease could not deny us. For her, I participated in yearly MS Walks along the Playland Parkway, volunteered at the famous Tappan Zee MS Bike Tours, and attempted MS Climbs to the Top at Rockefeller Center and Citi Field that took my breath away (in more ways than one).

Just as Mom refused to be defined by her illness, I refused to be defined as the son of an ill mother, and I survived well into my adulthood thinking I was largely unscathed by the cards I was dealt. If anything, I processed my mom’s MS as a point of pride and a subjective utility — a prized arrow in my quiver that I alone among my friend group possessed — good for jumping the lines at amusement parks and airports, as fodder for a college admissions essay, or for a guaranteed shot of sympathy from a romantic interest.

At the height of my self-analysis, I reasoned that due to the behaviors I saw modeled by my dad in how he so dutifully cared for his sick wife, it might be my destiny to end up with a partner in a similarly compromised state of health. I noticed myself attracting girlfriends who struggled with eating disorders, addictions, and other self-destructive patterns who triggered my ‘savior syndrome,’ finding what I saw as their need to be rescued and protected strangely arousing.

Approaching 40 and experiencing an unshakeable sense of rudderlessness after my umpteenth failed relationship, I decided it was time to get serious about working on myself. I signed up for a seven-day “personal transformation retreat” offered by the Hoffman Institute in the bucolic Sonoma Mountains of Northern California.

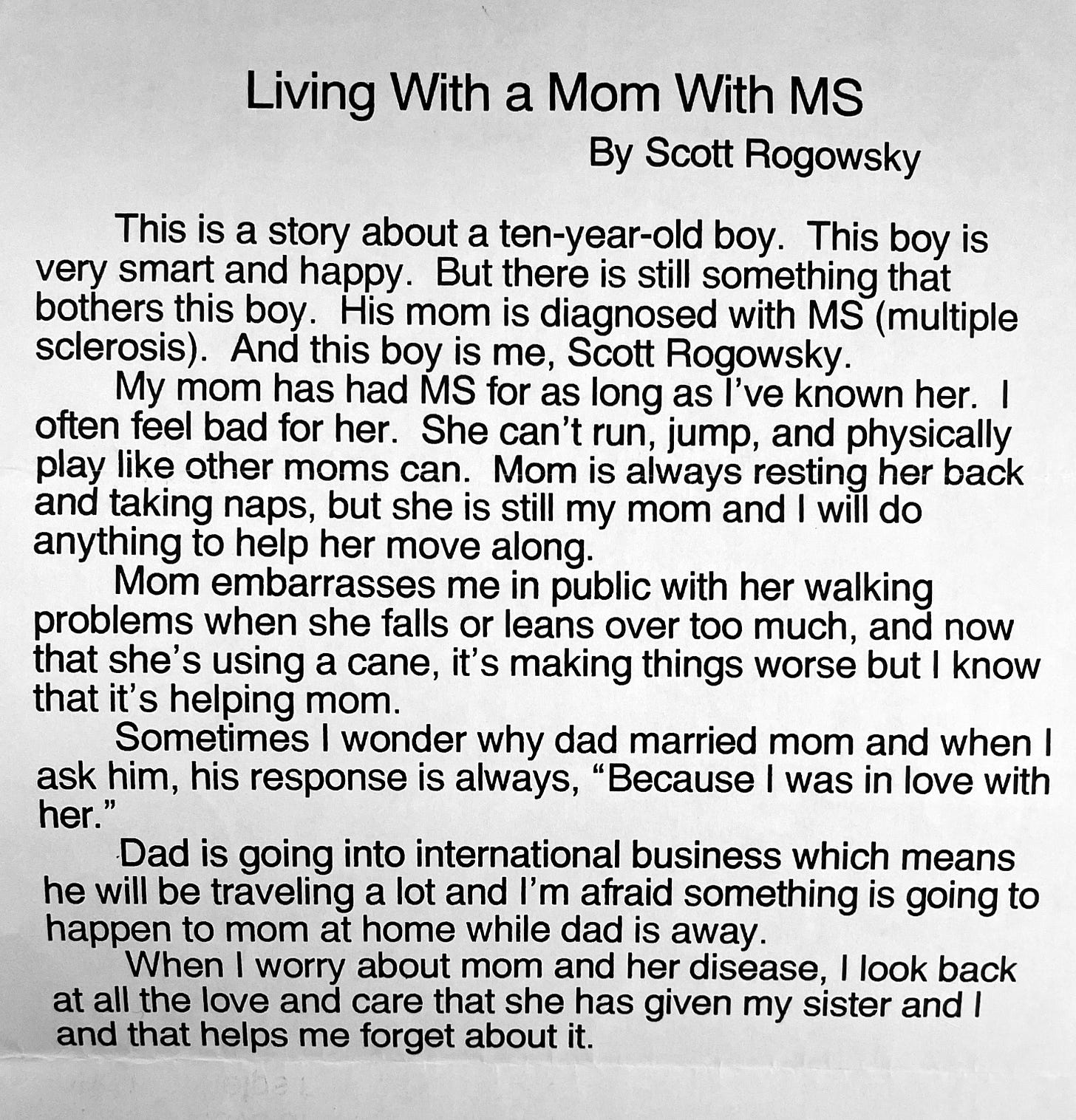

While completing the all-important homework assigned before embarking on the retreat, in which I lovingly and profoundly contemplated my parents’ patterns of behavior and traced those back that I identified as my own, I was gifted with a serendipitous discovery Mom made while cleaning up some papers in her office: a short story I wrote in fifth grade of which I had zero recollection, called Living With a Mom With MS.

On my second day at Hoffman, I had my first one-on-one meeting with my small group instructor Regina. She had read my homework, and I had shared with her this time-capsuled bombshell from my ten-year-old self. When I started to confide in her that I wasn’t sure if this retreat was for me, since I didn’t feel like I had experienced any trauma of the magnitude that I had heard shared by my classmates — suicide, physical and sexual abuse, absent, alcoholic or drug-addicted caregivers — Regina looked me in the eyes and said, “Honey, your mother is your trauma. Explore that.”

And so I did. Sans any external distraction (Hoffman faculty confiscated our electronic devices, deprived us of art and music, and bade us not to exercise, practice yoga, or consume non-essential medication or recreational substances), I was able to sit quietly with myself, get to know and integrate all aspects my Self (my body, my intellect, my emotional child, and my Spirit), and work with these aspects to interrogate my imprinted beliefs and patterns and ponder the deepest questions of my being.

With the help of guided visualizations, I was able to conjure that ten-year-old me in a form as tangible as my most lucid dreams. I was able to hold him and let him express the emotions he had suppressed for so long. I let him cry uncontrollably on my shoulder as he vented his dizzying array of feelings: frustration and anger and shame and self-pity and self-loathing and helplessness and existential confusion.

He said he didn’t ask to be born to a mom with MS. He said it was selfish and unfair of Mom and Dad to even have children — that they did it “for them,” without fully considering how their kids would be affected.

I told him his feelings were valid. I told him that what we were doing — cleansing our system of emotional toxins that been kept in cold-storage for decades — was healthy. I told him it was all going to be okay, because it was.

The retreat is called the Hoffman Process, and for good reason. It’s a process that doesn’t merely last the seven days up in the mountains; it’s a daily practice that forms a lifelong process of continuing personal growth, ever-greater understanding and self-knowing, and a ceaseless dedication to radiating self-love.

Through my process, I have come full circle on my feelings around what it’s like to live with a mom who lives with MS. I came to understand that perhaps my mom’s disease had defined me more thoroughly than I had let myself believe. In holding and healing my inner child — so vividly embodied thanks to his own heartbreaking words — I was able to release all resentment, realizing that just as I never wished to be born to a sick mother, my mother never wished to be sick.

I am proud to say on this special day of Tobi’s Diamond Jubilee that I have not only reached a place of full acceptance around my mother’s condition and my subsequent relation to it, but I have reached a deeply spiritual appreciation for her disease and the impact it had on me. Today, I can honestly say that I am grateful for her MS — for her embarrassing public accidents, for all her daily naps, for all her struggles to walk from her bed to the bathroom, for all the cumulative months she’s spent in hospitals and rehab facilities, for all the close calls, for all the tears.

Why? Because I can finally accept that it all happened. It’s not fun that it happened. But there is no denying that it did happen, and neither I nor Mom — nor Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Warren Buffett, Juan Soto and Shohei Ohtani with all their money combined — do anything to make it not have happened.

In unconditionally accepting the reality of what happened, and given a choice of how to feel about it, I choose glad over sad. Appreciation and gratitude over resentment and self-pity. It simply strikes me as the happier, healthier option.

How could I feel anything but pure gratitude for being born to a husband and wife so madly in love that they felt compelled to create a family — a sacred expression of their love — despite the overhanging specter of an undoubtedly diminished future?

How can I not appreciate that everything that I have witnessed and experienced is exactly what I was supposed to witness and experience? That the totally unique circumstances of my life and their infinite chain of causes and effects has made me exactly who I am, exactly who I’m supposed to be?

Because if it didn’t all happen the way it did — if I was born to Christine Brinkley and Billy Joel, or Princess Diana and Prince Charles, or Bob and Joan Goldblatt — then I wouldn’t have become the man I am today: a man who cares deeply, who gives generously, who loves abundantly… and who maybe turned out to be kinda funny because he subconsciously sought refuge in comedy as a self-coping mechanism?

So let’s raise a glass… Happy Birthday, Mom! To 75 more!

Thank you for being you, and for being so utterly essential in my being me.